Celebrating Indigenous Heritage

Archives of Indigenous Peoples Day

Celebrate this annual holiday with us in honor of all of our ancestors, the people continuing the struggle today and future generations.

Part 3 - Resistance 500 & The First Indigenous Peoples Day

The Bay Area Regional Indian Alliance & Resistance 500 1991

Nilo brought two people with him, neither of whom I knew until then: Antonio Gonzales and Millie Ketcheshawno. Tony was director of the International Indian Treaty Council (IITC); Millie had played an important role in the Alcatraz Island occupation of 1969-1971, and had been the first woman director of Intertribal Friendship House in Oakland (a primary center for the Bay Area Indian community). Tony was Seri/Chicano, and Millie was Muscogee. Neither Tony nor Millie had been to the Encuentro, but both would play important roles in the events to follow.

Neither the IITC nor AIM had been an organizing group of the Quito Encuentro. Historical and cultural differences apparently had caused distance between North American and Latin American Indigenous organizations. The histories of domination and oppression by the different north/south colonial powers had taken very different turns, resulting in many obstacles hindering the respective Native peoples’ mutual understanding. The Encuentro organizers had apparently tried to sidestep those problems by making SAIIC the North American organizing group, even though SAIIC was not based in northern Native peoples. As a result, all US and Canadian people at the Encuentro, including those affiliated with IITC and AIM, had attended as individuals, not as organizational representatives.

But back here in the Bay Area everything was different. Nilo must have realized that to proceed, SAIIC had to form a coalition with the Northern Native nations’ progressive organizations, such as IITC and AIM, and that is what SAIIC did.

In 1990, as today, the Bay Area was home to one of the largest concentrations of urban Indians in North America. Around 40,000 Native Americans of many tribes and nations lived in the area, as well as 800,000 Latinos, most of whom were part or wholly Indigenous.

At the meeting in the mayor’s office, Nilo and I reported to Loni about the Quito Encuentro. Millie and Tony already knew about it, since word had spread quickly in the Indigenous community. Then the four of us passed the next hour or so brainstorming about how to proceed.

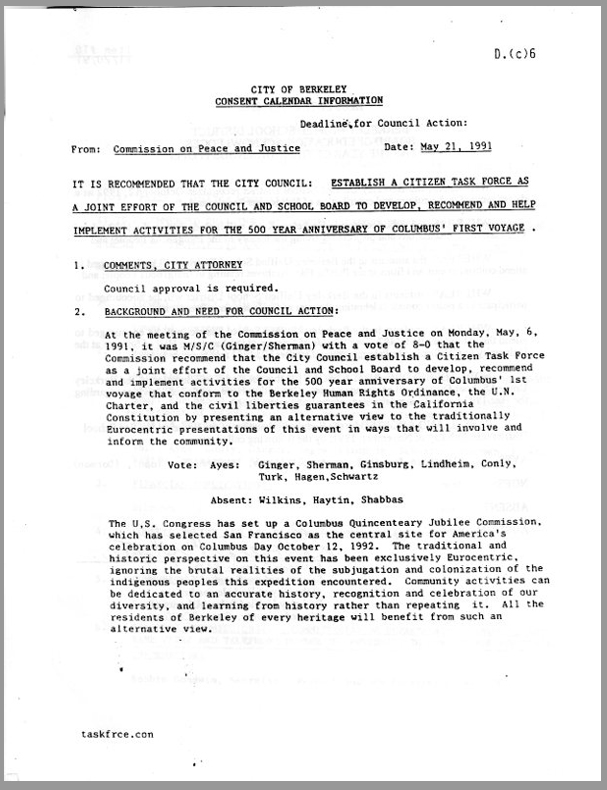

Loni suggested that we needed to get the city to set up an official “task force” to study the issues and report findings and recommendations. First we would need to thread our way through the city processes of boards and commissions. The most important bodies would be the Peace and Justice Commission and the School Board. If we could garner their support, they would report to the city council, and that would open the door to the council setting us up as an official task force. Loni offered to find us a space in city hall to work out of, if we needed it.

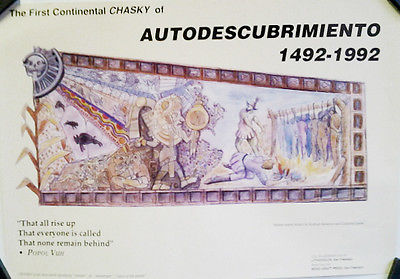

Poster by Rodrigo Betancur and Elizabeth Dante

First Chasky (Huracán Fall/Winter 1990)

The following year, on October 12, 1991, with Luis Vasquez as the central organizer, the Chasky reversed the route, beginning in Garfield Park and finishing in La Raza Park. It again used “a variety of performances and visual art as a strong statement of cultural, spiritual, and political identity,” and meant to be “a rallying point and touchstone for many groups… to work in harmony to dedicate the next twelve months to opposing the quincentenary celebrations in 1992.”

We would adapt the chasky concept into the events of the first Berkeley Indigenous Peoples Day in October, 1992.

The first Chaskys did not actually declare the event to be a celebration of Indigenous Peoples Day, even though it included the same themes. At the time of the first Chasky, in October, 1990, the concept of Indigenous Peoples Day was still germinating where it lay since 1977, when it was originally declared by the Geneva UN Indigenous conference, and I for one was not even very aware of the 1977 Geneva conference at that time. Even the Quito Encuentro, although all the participants resolved that they would turn October 12, 1992 “into an occasion to strengthen our process of continental unity and struggle towards our liberation,” never actually declared that henceforth October 12 would be celebrated as Indigenous Peoples Day.

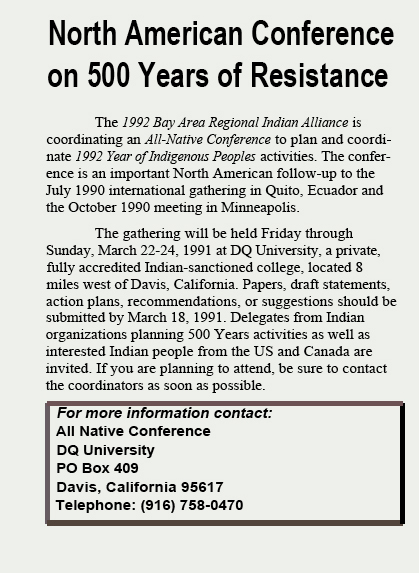

Indigenous Peoples Day would resurface again in March, 1991, at the D-Q All-Native Indigenous Conference.

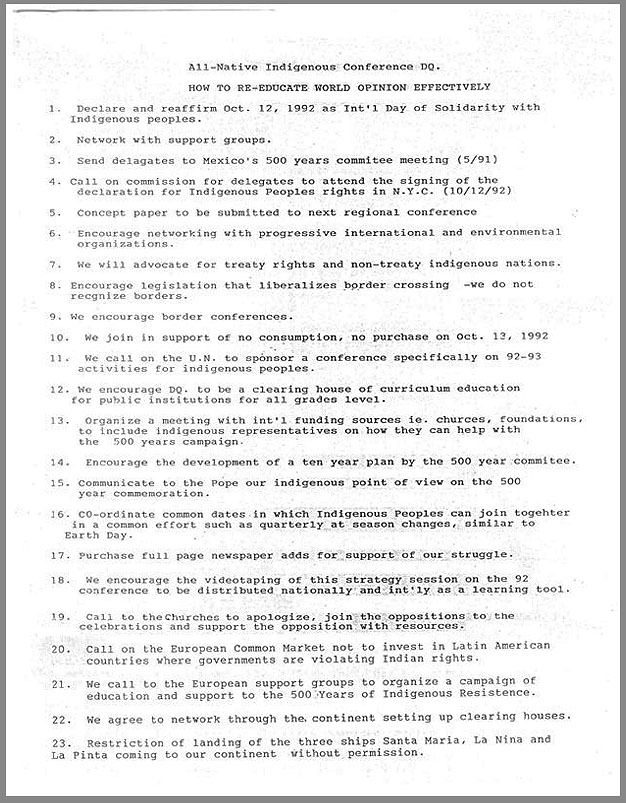

D-Q All-Native Indigenous Conference

Bay Area Regional Indian Alliance (BARIA)

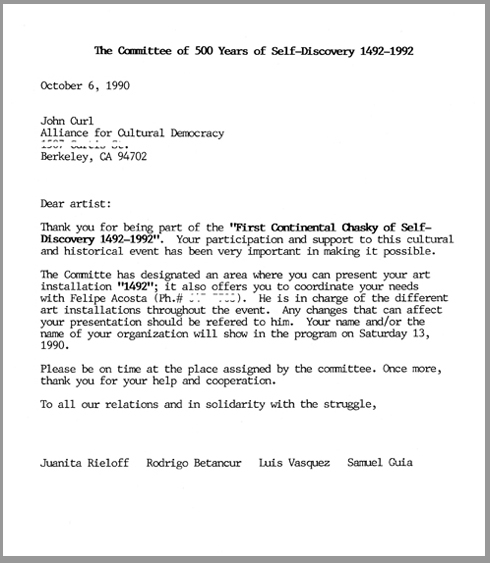

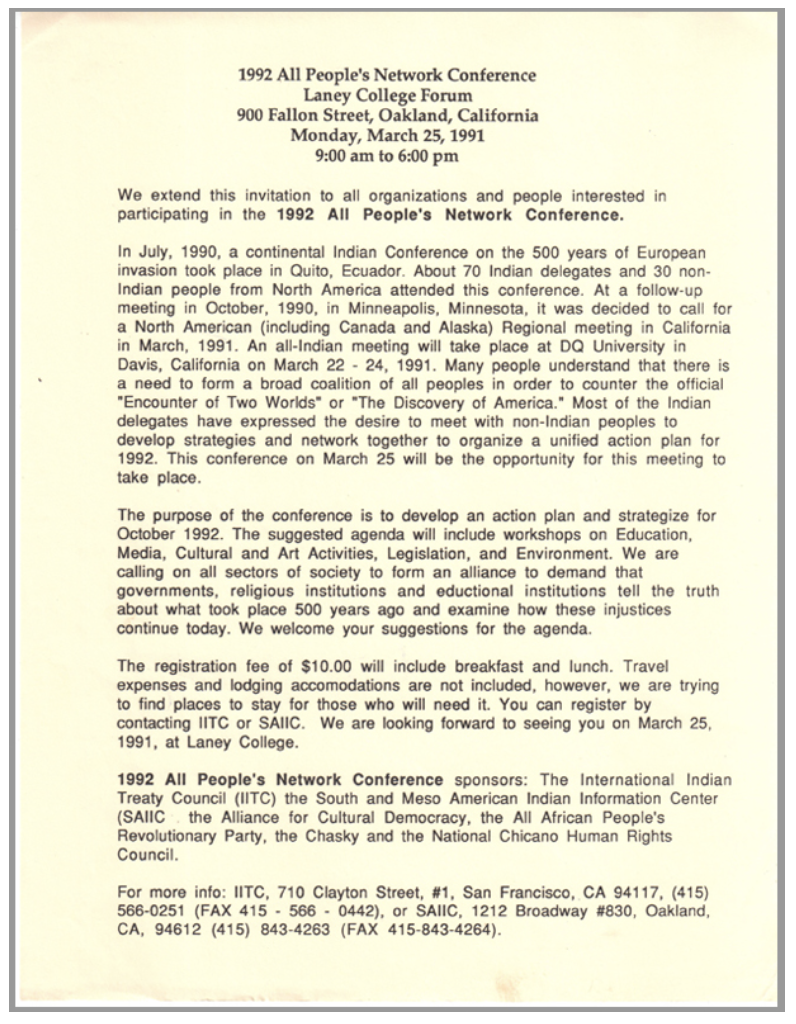

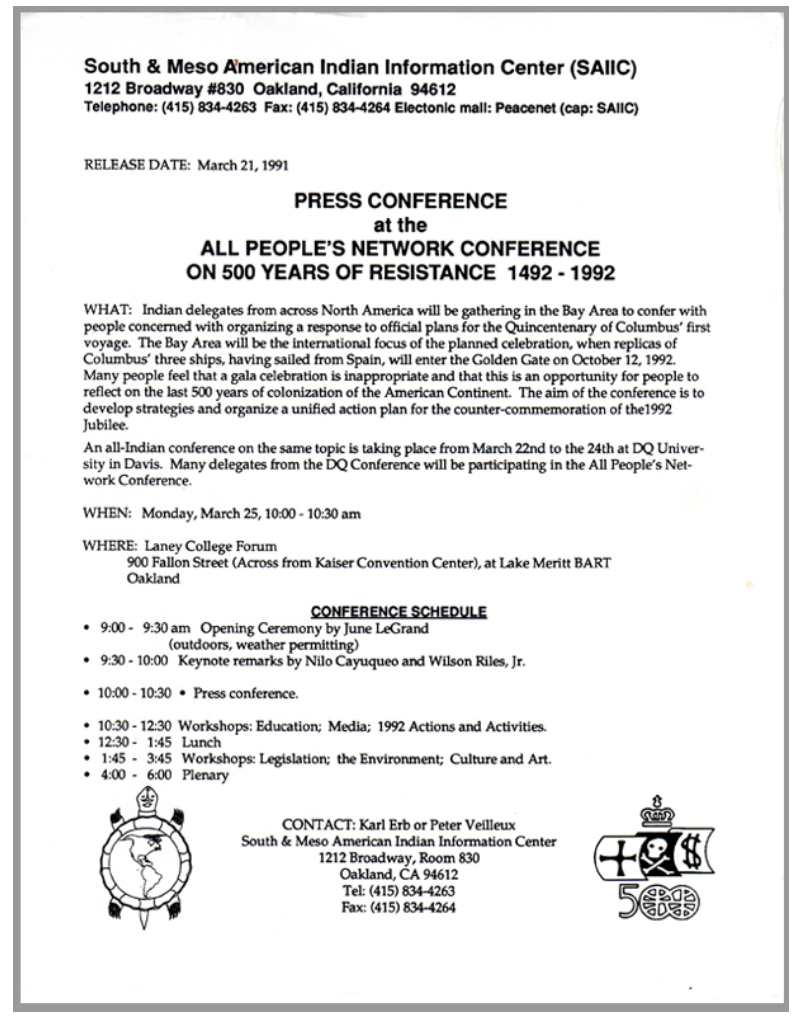

The all-Indian conference was scheduled for March 22-24, 1991. The follow-up one-day conference with nonIndian people was to take place on the next day, at Laney College in Oakland. To host the D-Q All-Native Indigenous Conference, they formed a coordinating group called the 1992 Bay Area Regional Indian Alliance.

Abya Yala News (SAIIC)

On March 22, over one hundred North American Indian representatives came together at D-Q, and consolidated the fruits of many months of intense organizing in their communities. The main organizers were SAIIC, IITC, Intertribal Friendship House, Seventh Generation Fund, and the Santa Clara Indian Valley Council. The conference divided into six work commissions: Action plan for 1992 and beyond; Indian prisoners and freedom of religion; Environment; Education; Communication and Media; Respect and care of Indian families and children.

At the end of three days of discussions, the All-Native Indigenous Conference resolved:

1992 All People’s Network Conference

The invitation to the All Peoples Conference stated that the mission of the event was “to form a broad coalition of all peoples in order to counter the official ‘Encounter’ of Two Worlds or ‘The Discovery of America.’”

“The purpose of the conference is to develop an action plan and strategize for October 1992. The suggested agenda will include workshops on Education, Media, Cultural and Art Activities, Legislation, and Environment. We are calling on all sectors of society to form an alliance to demand that governments, religious institutions and educational institutions tell the truth about what took place 500 years ago and examine how these injustices continue today. We welcome your suggestions for the agenda.”

The conference sponsors were SAIIC, IITC, ACD, the National Chicano Human Rights Council, the Chasky, and the African People’s Revolutionary Party.

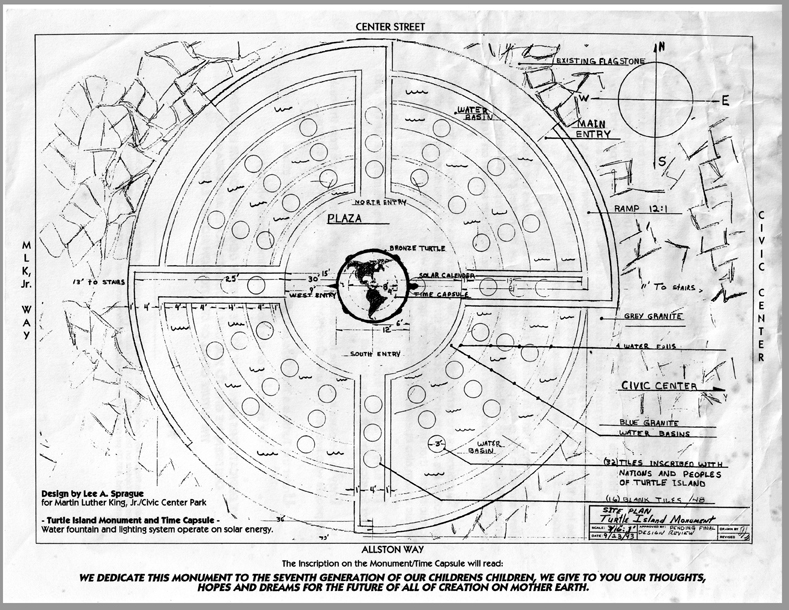

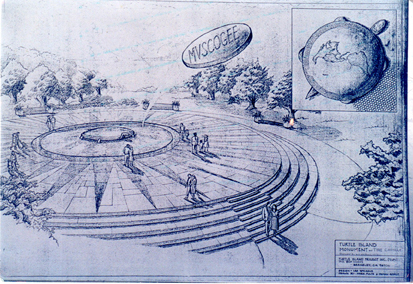

As I entered the conference, a very tall, powerfully built Native man with long braids pulled me aside, introduced himself, and said he wanted to show me something. Lee Sprague, Potawatomie from Michigan, member of the Little River Bank of Ottawa Indians, unrolled a set of architectural plans for what he called the Turtle Island Monument, a large sculpture of a turtle surrounded by plaques with the names of Native nations, and beneath it, a time capsule. Turtle Island was the American continent. According to Lee, there was no monument to Native people in this country, so he was gathering support to have it built, and he had heard that Berkeley might be a possible place. He introduced me to the architect, Marlene Watson, Navajo. We chatted for a while as the auditorium filled.

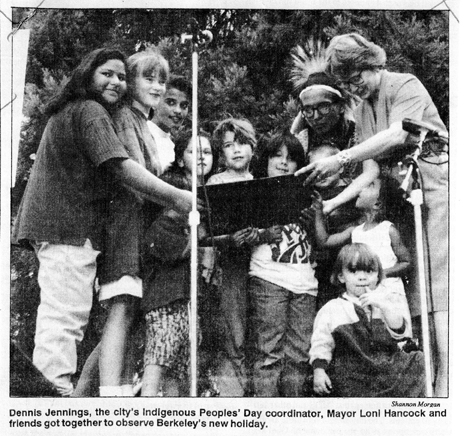

I saw Millie Ketcheshawno with a group and touched base with her. She introduced me to Dennis Jennings, a Sac and Fox man who had been with her on Alcatraz during the 1969-1971 occupation, and later worked for IITC before Tony Gonzales became director. With Dennis and Millie were Bernadette Zambrano, Lakota Hardin, and several others. I also met Gabriel Hernandez and Ariana Montes, from the National Chicano Human Rights Council and the Chicano Moratorium; Dorinda Moreno, organizer for the Peace and Dignity Journeys; and Nina Serrano, who had a show on KPFA radio. All of these people, and others I met that day, would make important contributions to the counter-quincentennial and Indigenous Peoples Day.

The conference opened with a ceremony of burning sage, led by two spiritual leaders who had also attended the Quito Encuentro: June Le Grande and my old roommate and mentor Ed Burnstick.

June was also the keynote speaker: “We need to bring out the truths of history and of the present, for the sake of all the unborn generations,” Le Grande said. “We’ve got to educate the educators. Our schools need to teach the facts, not the falsehoods that fill many of the books today.”

Inspired speeches by SAIIC director Nilo, Oakland Councilmember Wilson Riles, Jr., and Betty Kano, National Coordinator of ACD, detailed how the invasion that Columbus led caused devastation to Indian civilizations, and how this oppression continues today.

“After all the destruction and violations of human rights, repression of indigenous people and devastation to the earth,” Nilo said, “they are trying to impose a New World Order, which for us is the same order of oppression we have been suffering under for 500 years. We need to say ‘no’ to the official celebration.” [3]

Betty Kano said, “The 500 Years of Resistance challenges us to struggle together against the New World Order and to work together for the future of the planet for the next 500 years.”

Riles, a leader in the Bay Area Free South Africa Movement, proposed that the Quincentennial get back to the original meaning of the Biblical word “Jubilee,” which signified that every fifty years all land would revert to its original owners and all debts would be forgiven.

At the press conference that followed, Tony Gonzales explained, “The D-Q gathering planned major events on behalf of our ancestors, those that have gone before us. And it is from this spiritual and inspired position that we will move the agenda forward for 1992 and beyond, all for the love of our coming generations.”

We spent most of the rest of the day in workshops, three in the morning and three in the afternoon. The morning workshops were: 1992 Activities, Actions and Networking; Media; and Education. In the afternoon were Legislation; Environment; Culture and Art. Each workshop developed an action plan for its area of discussion.

Then at 4:15 each workshop reported back to the plenary.

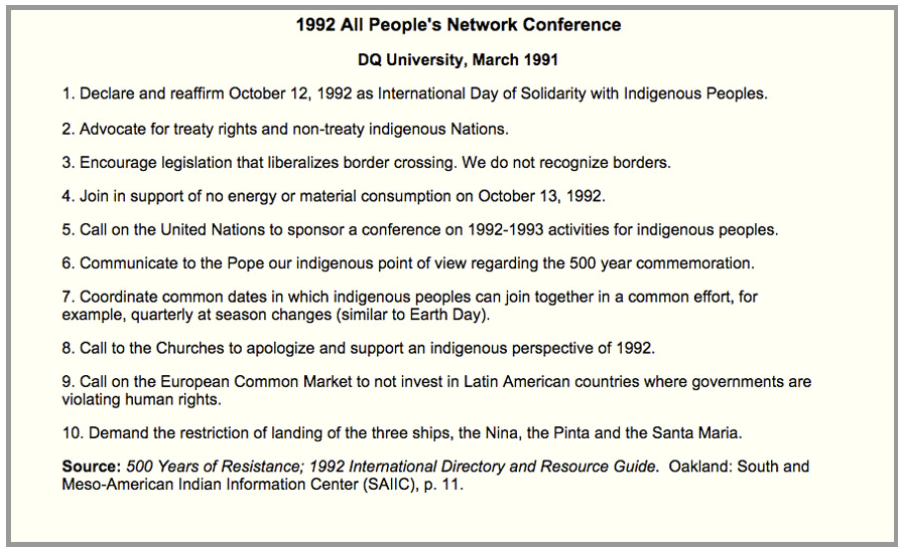

After hearing all the reports and recommendations, the plenary basically affirmed and consolidated the most important resolutions of the earlier All-Native Conference at D-Q:

1992 ALL PEOPLE’S NETWORK CONFERENCE

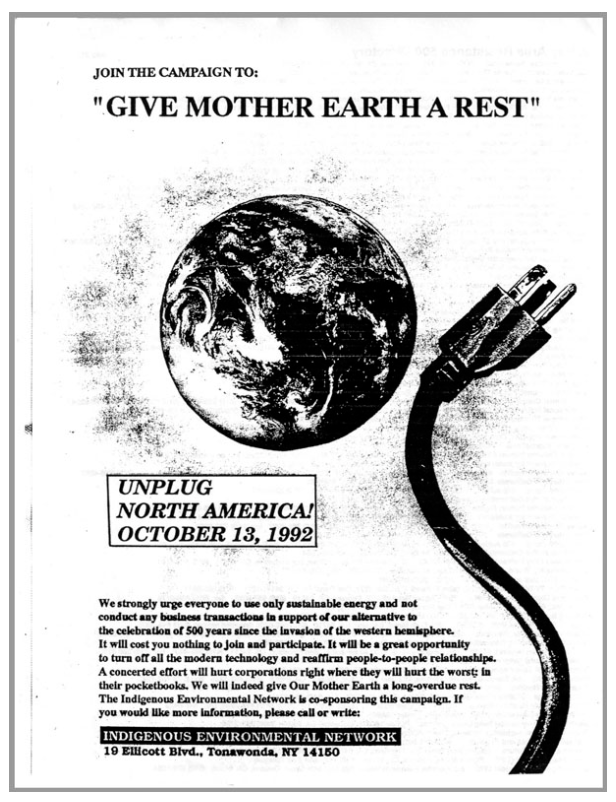

- Declare and reaffirm October 12, 1992 as International Day of Solidarity with Indigenous Peoples.

- Advocate for treaty rights and non-treaty indigenous Nations.

- Encourage legislation that liberalizes border crossing. We do not recognize borders.

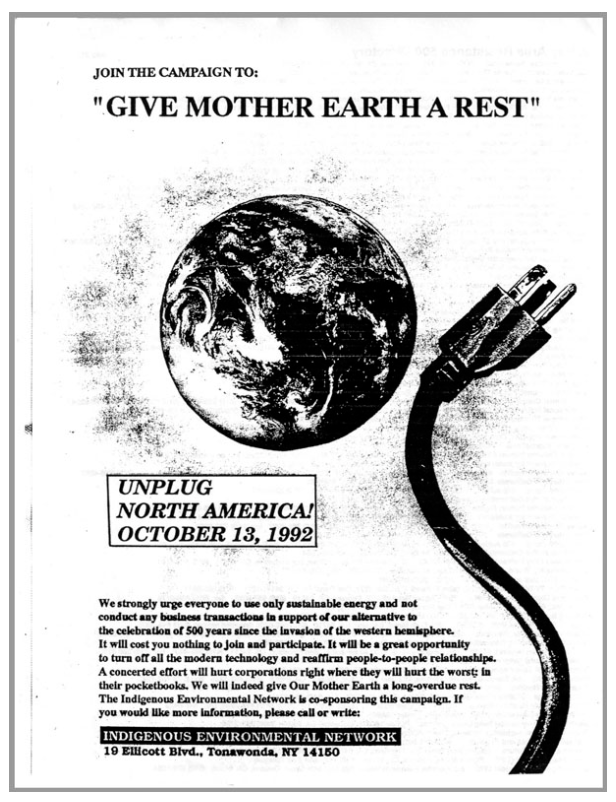

- Join in support of no energy or material consumption on October 13, 1992.

- Call on the United Nations to sponsor a conference on 1992-1993 activities for indigenous peoples.

- Communicate to the Pope our indigenous point of view regarding the 500 year commemoration.

- Coordinate common dates in which indigenous peoples can join together in a common effort, for example, quarterly at season changes (similar to Earth Day).

- Call to the Churches to apologize and support an indigenous perspective of 1992.Call on the

- European Common Market to not invest in Latin American countries where governments are violating human rights.

- Demand the restriction of landing of the three ships, the Nina, the Pinta and the Santa Maria.

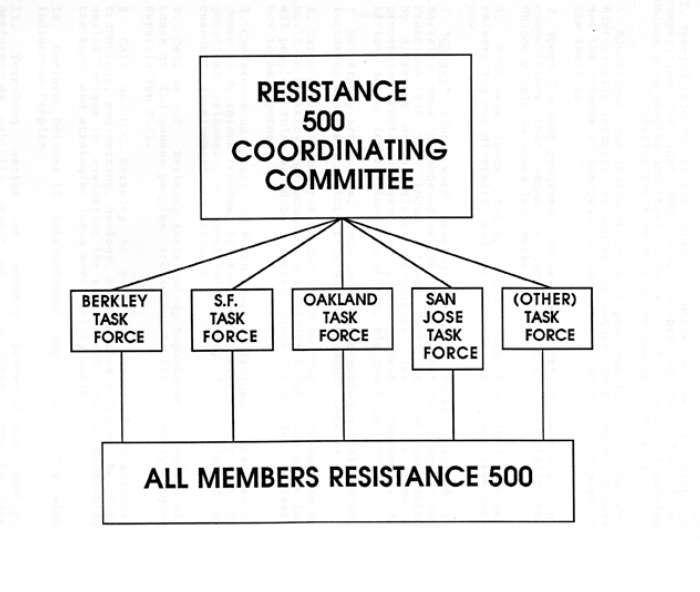

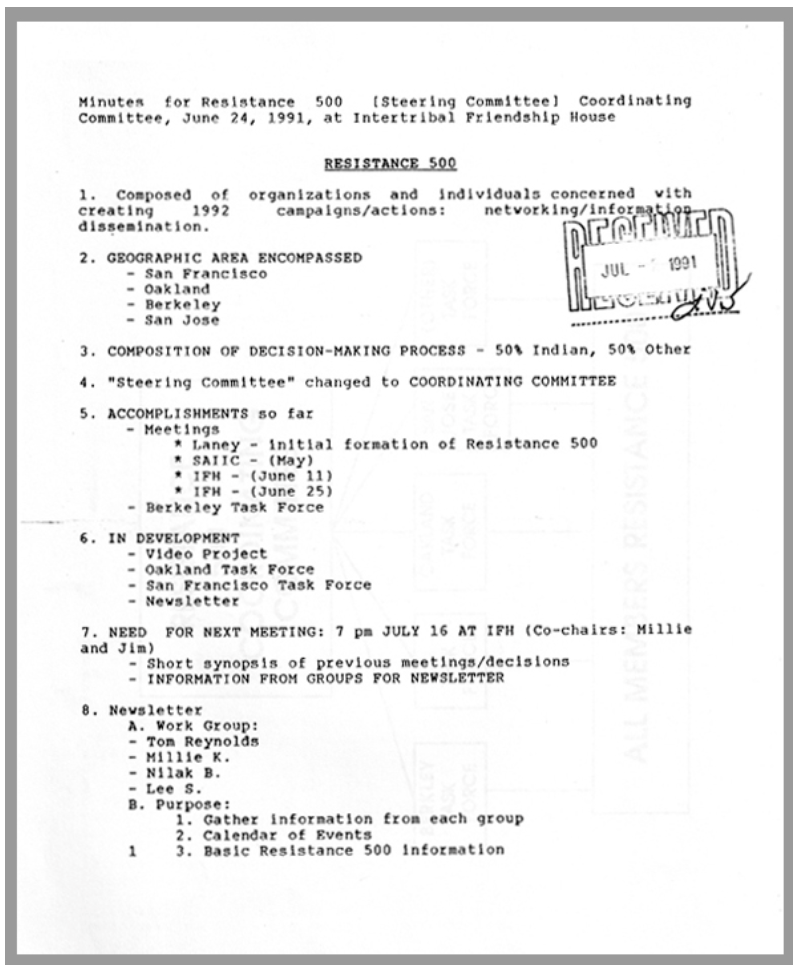

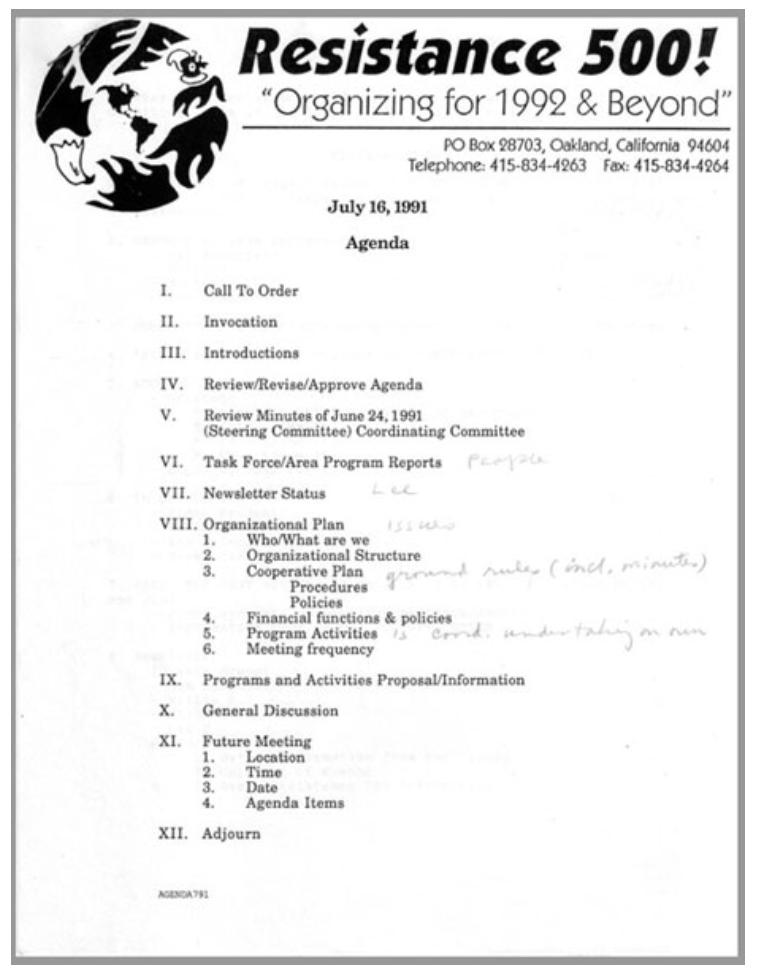

We empowered the conference organizers to proceed with follow-up meetings leading to actions. We divided the Bay Area into five task force areas: San Francisco, Oakland, Berkeley, San Jose, and Other. Almost everyone signed up to join a task force. So at the end of deliberations a new all-people coalition emerged on March 25, 1991, RESISTANCE 500, with a plan for leading coordinated actions to counter the officially planned “Jubilee” commemoration of Columbus’s invasion.

Resistance 500

Each local Resistance 500 task force began to hold meetings, and once a month we all came together at Intertribal Friendship House (IFH) in Oakland, to report on our progress, exchange ideas, and coordinate efforts.

The Bay Area urban Indian community’s roots went back to the 1950s when large numbers of Native people from all over the US were lured off reservations and rural areas and brought here with promises of jobs by the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ Relocation Program, which was connected to their “termination” policy of disbanding all tribes by withdrawing recognition. Most of the early community were young single people and young families. West coast cities were focuses of the program, and the Bay Area wound up with one of the urban highest concentrations of American Indian populations in the nation. Indian people from many tribes, reservations and rural areas adjusted to urban living by creating a network linked by culture and shared experiences. Intertribal Friendship House, today one of the oldest urban Indian organizations in the country, became a sanctuary, a center for mutual self-help, nurturing numerous people through difficult times, a gathering place for both newcomers and their descendants.

The Friendship House Wednesday Night Dinner became a weekly social ritual binding the community together. IFH emerged as the heart of a new, cooperative, multi-tribal Indian community. A new intertribal personal identity of “urban Indian” emerged. It was only natural that IFH became the center for Resistance 500 organizing, with the hospitality of Jim Lamenti, the director, his wife Evelyn Lamenti, Susan Lobo, Carol Wahpepah, Betty Cooper, and all the numerous IFH family. We held our meetings on Wednesday nights, after the traditional dinner.

Berkeley Resistance 500 Task Force

In Berkeley, our growing group continued to follow through on the plans already in progress informally with Mayor Hancock, and we made presentations to different city commissions, who almost entirely greeted our efforts with enthusiasm. The Peace and Justice Commission and the School Board recommended to the Berkeley City Council to set us up as an official city citizen task force, “to develop, recommend and help implement activities for the 500 year anniversary…that present an alternative view to the traditional Eurocentric presentations of this event in ways that will involve and inform the community.”

City Council Sets Up Task Force

So the Berkeley City Council voted unanimously to approve the Berkeley Resistance 500 Task Force as an offical city body. They empowered us to investigate the issue of the upcoming Quincentennial, and asked us make recommendations as to how the city of Berkeley should respond.

At that point our real work real just beginning. We already knew that we were going to propose replacing Columbus Day. But we needed to educate and lobby every public body in the city to gain citywide support for the idea that Indigenous Peoples Day fitted with the values of the people of Berkeley much more than celebrating Columbus with a holiday.

From the beginning we decided that our group would be at least 50% Indigenous, which we almost always accomplished, without ever turning anyone away for that reason. We used a simple consensus decision making process, with the stipulation that on specifically Indigenous questions only Native people would be the decision makers, while nonNative people would step aside.

Many people participated in the Berkeley Resistance 500 Task Force that first year, and in its subsequent transformation into the Berkeley Indigenous Peoples Day Committee. Among the regulars were Dennis Jennings, Millie Ketcheshawno, Lee Sprague, Bernadette Zambrano, Gabriel Hernandez, Ariana Montes, Ken Roubideaux, Marlene Watson, Nancy Gorrell, Mark Gorrell, Bonita Sizemore, John Bellinger, Marilyn Jackson, Patricia Brooks, Roberto José García, Betty Kano, Pennie Opal, Nancy Delaney, Les Hara, Paul Bloom, Mary Ann Wahosi, Nancy Schimmel, Diane Thomas, Eileen Baustian, Alfred Cruz, Audry Shabaas, Barbara Remick, Beth Weinberger, Beverly Slapin, Cece Weeks, Chris Clark, Cindy Senicka, Susan Lobo, Garrett Duncan, Jennifer Smith, Jos Sanchez, Judy Merriam, Lincoln Bergman, Michael Sherman, Noele Krenkel, Robert Mendoza, Regina Eisenberg, myself, and many more.

Part of the Berkeley Resistance500 Task Force at a meeting.

L-R Back: Noele Krenkel, Dennis Jennings, John Curl, Nancy Gorrell, _____.

Center: Mark Gorrell, Bernadette Zambrano, Nancy Delaney, Roberto José García

Front: Patricia Lai Ching Brooks, Gabriel Hernandez, Ariana Montes

[Photographer unknown]

We elected Dennis Jennings to be the Coordinator of the first Berkeley Indigenous Peoples Day, for which we paid him a very modest stipend, primarily out of the grant from the city, supplemented by small grants from the Vanguard Foundation and the Seventh Generation Fund. Dennis was our unanimous choice because of his strong leadership qualities, his organizing abilities, his dedication to social justice, his commitment to Indigenous and environmental renewal.

Mayor Hancock arranged for Dennis to work out of a desk at city hall, graciously provided by Councilmember Nancy Skinner in her office. Mark Gorrell knew how to steer our way through the city labyrinth very well from his work at the Ecology Center and as an architect, and I knew the city machinery from my work on the West Berkeley Plan and as a member of the Berkeley Citizens Action steering committee. The Gorrells’ house became our regular meeting place.

Other R500 Activities

The San Francisco, Oakland, and San Jose Resistance 500 groups also lobbied their mayors and councils to set up city task forces similar to Berkeley’s, but without success. Nevertheless all the groups continued moving forward together. The Resistance 500 coalition continued to hold monthly coordination meetings at Intertribal Friendship House, to plan, coordinate, and carry out activities around the Bay.

It seemed like almost every progressive cultural and political group was coming on board Resistance 500. Although all were not totally coordinated, all fed energy into each other. Since the Bay Area was the scheduled center of the national Quincentennial “Jubilee” celebration of imperialism, colonialism and genocide, the region also became central to the resistance. Many events began to take shape. The counter-quincentenary movement in the Bay Area became a whirlwind of activities. The level of excitement was very high, in part because the official Quincentennial “Jubilee” was so odious.

This archive and narrative is focused on Berkeley partly because we were the only group who actually succeeded in instituting permanent changes through our city council. However, numerous groups accomplished important and consciousness raising activities focused on 1992.

The Resistance 500 Directory eventually listed 85 affiliated groups.

IITC Alcatraz Sunrise Ceremony

The 1969 occupation of Alcatraz island in San Francisco Bay, still physically dominated by the deserted prison, by a group of Native college students calling themselves Indians of All Tribes, was the spark that reignited North American Indian activism and the catalyst for many profound and permanent changes. It transformed how Native people saw their own culture, rights, and identity; it changed the relationship between Native and nonNative people in the US; it led to the transformation of the federal government’s policy from genocidal “termination” to Indian self-determination. The importance of Alcatraz cannot be overstated. We in Resistance 500 were most deeply honored that Millie Ketcheshawno, Dennis Jennings, and others involved with the original occupation were now participating closely in our project.

In 1975 the International Indian Treaty Council had begun the annual tradition of commemorating the 1969-1971 occupation of Alcatraz with a sunrise ceremony on the island, every unThanksgiving Day.

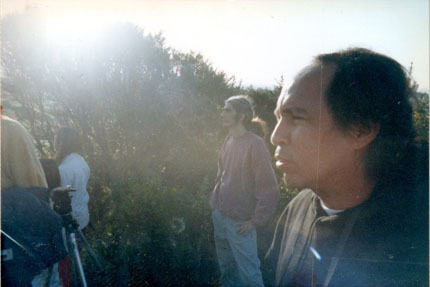

Then on October 12, 1991, IITC initiated the tradition of a second sunrise ceremony on Alcatraz Island, celebrating Indigenous Peoples Day. On that occasion around 300 people, our Berkeley group among them, ferried from San Francisco to the island, and participated in the sacred ceremonies beside the ceremonial fire. Since this is Ohlone land, representatives of that nation served as host and welcomed us.

[Photo by Nancy Correll][1]

UCB Lawrence Hall of Science Exhibition

We worked on the Unversity of California’s Berkeley Lawrence Hall of Science exhibition “1492: Two Worlds of Science,” which ran between October, 1991 until January, 1992. They hired Lee Sprague as a consultant. With Lee’s assistance, the result focused on many of the core issues. As a newspaper article at the time described, “The exhibits use science to address painful aspects of history, such as slavery, genocide and ecological destruction, that often have been overlooked in discussons of Columbus’ exploration.”

![B-R500-Pic-2 Lee Sprague at the Lawrence Hall of Science exhibit. [SF Chronicle 10/10/91]<br />](http://bevy41.sg-host.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/B-R500-Pic-2.jpg)

Berkeley City Council Officially Institutes

INDIGENOUS PEOPLES DAY

The Berkeley Resistance 500 Task Force walked the concept of Indigenous Peoples Day through the city commissions until we finally reached the Berkeley City Council on October 22, 1991. On that date the city council voted unanimously in our favor, and made Indigenous Peoples Day an official Berkeley holiday when you didn’t even have to pay for parking meters, beginning the following year, in 1992. They also gave us a small grant to help cover our expenses in organizing events for the year.

Declaration of the City Council of Berkeley, California, Concerning

Indigenous Peoples Day

as proposed by the Berkeley Resistance 500 Task Force and Peace & Justice Commission

Passed Unanimously October 22, 1991

October 12 as Indigenous Peoples Day

The Berkeley City Council declares October 12 to be commemorated annually in

Berkeley as Day of Solidarity with Indigenous People

The First Commemoration. October 12. 1992

The Berkeley quincentennial commemoration of October 12 will be an all-day event

on the nearest calendar weekend, with ceremonies, cultural events and speakers,

participation from the schools and an informational procession.

1992 the Year of Indigenous People

The City Council declares that 1992 will be commemorated as the Year of

Indigenous People. The Council suggests that community organizations,

businesses, religious organizations, city commissions, parks, local radio, cable TV

stations and newspapers participate in this year and day; and that newspapers,

radio and cable stations issue regular reminders tbroughout the year of

Indigenous issues and events.

The Schools

The Council encourages the schools to include classroom discussions and projects

regarding the history and issues of the 500 years .

Public Libraries

The Council encourages the public libraries to participate with a series of

activities and events, including an invitation to Indigenous speakers, special

exhibits featuring literature of and about Indigenous peoples, and exhibits

critically displaying existing literature. The library should seek Indigenous

resource people to consult with them on obtaining and stocking progressive

literature.

Museum Exhibits and Events

The Berkeley Resistance 500 Task Force should consult with the museums to

encourage all exhibits connected with the Quincentenary to reflect the points of

view and concerns of Indigenous people.

The Arts

Galleries, cultural centers, theaters, bookstores are all encouraged to feature local

Native American artists througbout the year.

The University of California

The Council calls on the Anthropology Department to complete its returning of all

bones of Indigenous people; and encourages the University to establish a ‘think

tank’ composed of Native and non-Native academics to assist Indian struggles.

Monument and Time Capsule

The City will sponsor, by providing space and assistance, a monument dedicated

to the Indigenous peoples impacted by the arrival of Columbus. The monument

might include a time capsule storing Native tbougbts and artifacts for future generations.

Solidarity and Outreach

We encourage the people of Berkeley to reach out in solidarity with Indigenous

peoples around the world and their struggles, including especially people

indigenous to this local area and surrounding regions, to promote the health,

education and welfare of all people, both immigrant and Indigenous.

However, two of the more conservative council members were subsequently lobbied heavily behind the scenes by the opposition, who never actually showed much of a public face. Those council members returned at their next meeting with a counter proposal to bring back Columbus Day as a joint holiday with Indigenous Peoples Day. But they really had little public support, so the opposition quickly faded.

Berkeley School Board

Soon after the City Council acted, the School Board added their support of a year of educational activities in the schools.

Berkeley Public Library Exhibition

We set up an exhibit in the front windows of the downtown Berkeley library, and other exhibits in glass display cases inside the ground floor entrance way, that opened in January, 1992.

Loni organized a press conference in front of the library at the opening of the exhibit, with Dennis, herself, and the heads of the school board and the library. The press came out in force.

![Dnnis Jennings and Loni Hancock at press conference [Photo by John Curl]](http://bevy41.sg-host.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/B-R500-Press-Library-S-300x201.jpg) Dnnis Jennings and Loni Hancock at press conference [Photo by John Curl] [/caption]

Dnnis Jennings and Loni Hancock at press conference [Photo by John Curl] [/caption]

We continued organizing for community consciousness in a year of activities, focused on October 19, 1992.

Loni continued to give us her active support.

![B-R500-Pic-4 Loni receives an honor from Dennis Banks, Darrell Standing Crow, Millie Ketcheshawno,<br />

John La Velle, and Floyd 'Red Crow' Westerman. [SF Chronicle 3/7/92]<br />](http://ipdpowwow.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/B-R500-Pic-4.jpg)

John La Velle, and Floyd ‘Red Crow’ Westerman. [SF Chronicle 3/7/92]

Turtle Island Monument

Lee Sprague’s concept of the Turtle Island Monument took on a life of its own and had a separate trajectory throught the city processes. As public art and a proposed structure in Civic Center ML King, Jr. Park, it needed to pass through the Public Arts Commission and other agencies related to the parks. Lee had a powerful presence, projecting the rightness and purity of his vision, so doubters usually wound up excited supporters.

Lee told many times the creation story of Turtle Island according to his tribe. Almost every tribe had a version or variation of the story:

The Creation of Turtle Island

In my people’s creation stories the world was covered with water and all the animals were swimming. They were getting tired, so they respectfully asked the muskrat to go under the water to see if there was any earth. So the muskrat went down to find the earth. All of the animals were waiting for the muskrat to reappear. They were worried for the muskrat. Finally his body floated to the surface. The animals looked in his paw and they found some earth. They put the earth on the turtle’s back. The rest of the animals now knew that there was earth under the water so they each went down to get some earth, first the loon then the duck and all of the rest of the animals. They all put the Earth on the turtle’s back. This Is how Turtle Island was created.

The Bronze Turtle In the center of the monument symbolizes the creation of Turtle Island and sits in the center plaza. Many of the tiles have the names of Nations and Peoples who are Indigenous to Turtle Island. Many of the tiles are blank, representing the Nations and Peoples who are no longer here and the languages no longer spoken on Turtle Island.

Surrounding the center plaza, is a solar powered water fountain. The fountain symbolizes the Oceans and the Seas that surround Turtle Island, and Is powered by photo-voltaic system that uses the sun’s energy to move the water over the waterfalls. The photo-voltaic system also operates the lights in the evening.

The sun’s ray entering through the Turtle’s eyes and nose will mark the Summer and Winter Solstices and the Spring and Fall Equinox.

Entry to the plaza is from the four directions with the main entrance from the east The people who live here on Turtle Island with us came from these four directions.

Under the Turtle is a Time Capsule to be buried for seven generations.

The Inscription on the Monument/Time Capsule will say:

WE DEDICATE THIS MONUMENT TO THE SEVENTH GENERATION

OF OUR CHILDREN’S CHILDREN,

WE GIVE TO YOU OUR THOUGHTS, HOPES AND DREAMS

FOR THE FUTURE OF ALL OF CREATION ON MOTHER EARTH.

The dedication of the Turtle Island Monument would become the centerpiece of the events of the first Berkeley Indigenous Peoples Day.

Lee was confident that if the city would approve the concept, funds to build it could be gathered primarily or entirely from outside sources. So the cost of the project to the city was never an issue. Besides, the old fountain in the park, originally built in the 1930s, had been broken as long as anyone remembered and the general consensus held it to be just an eyesore, so nobody objected to replacing it with the Turtle Island Monument, at least not at that time.

Other Berkeley R500 Projects

We organized and participated in many projects over 1992.

On May 27, we put on a Cultural Festival of Poetry and Music at La Peña Cultural Center with fifteen poets.

On May 30 we organized a Multi-Cultural Book Fair at the gymnasium at Berkeley High School, with nineteen vendors, author book signings, poster sessions, storytelling, all day video showings. The R500 Education Committee, made up of Roberto José García, Gabriel Hernandez, Nancy Schimmel, Audrey Shabbas, and Jennifer Smith, were the central organizers.

![B R500 Pic 3 Jose Roberto José Garcîa at the Book Fair [Daily Californian, 1/14/92]<br />](http://bevy41.sg-host.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/B-R500-Pic-3-Jose.jpg)

Roberto José Garcîa at the Book Fair [Daily Californian, 1/14/92]

On July 29 we organized a Soapbox-Chautauqua at the Berkeley Unitarian Fellowship Hall, an open mike on quincentennial issues, a forum where people of different backgrounds stepped up one by one and spoke from the heart about indigenous peoples day. We did another Chautauqua on September 17.

We sponsored and some of us actually acted in a satirical play about Columbus at nearby Mills College.

Besides operating museums in the City, the University of California at Berkeley also operated the Black Hawk Museum of Art, Science & Culture in the town of that name, around 25 miles inland. A member of our group, Marilyn Jackson, pointed this out to Dennis Jennings, who was a descendent of Black Hawk, the great Sac and Fox chief. This led to Dennis and our group helping to organize a weekend of Indigenous events at that location the following spring, when the Blackhawk Museum was actually dedicated to the Sac and Fox Nation.

An equally important project of ours was helping to organizing a Berkeley-Yurok Nation “sister community” relationship. For that we worked closely with Sue Masten, who would be elected tribal chair and later president of the National Congress of American Indians (NCIA). A group of us traveled to the Yurok Reservation in northwestern California on the Klamath River near the Pacific coast, and were guests of their generous hospitality. The Berkeley City Council would approve the Yuroks as a sister community the following year.

The National Columbus Quincentenary

To understand the forces arrayed against us, we need to look more closely at what the US government was planning for October 12, 1992.

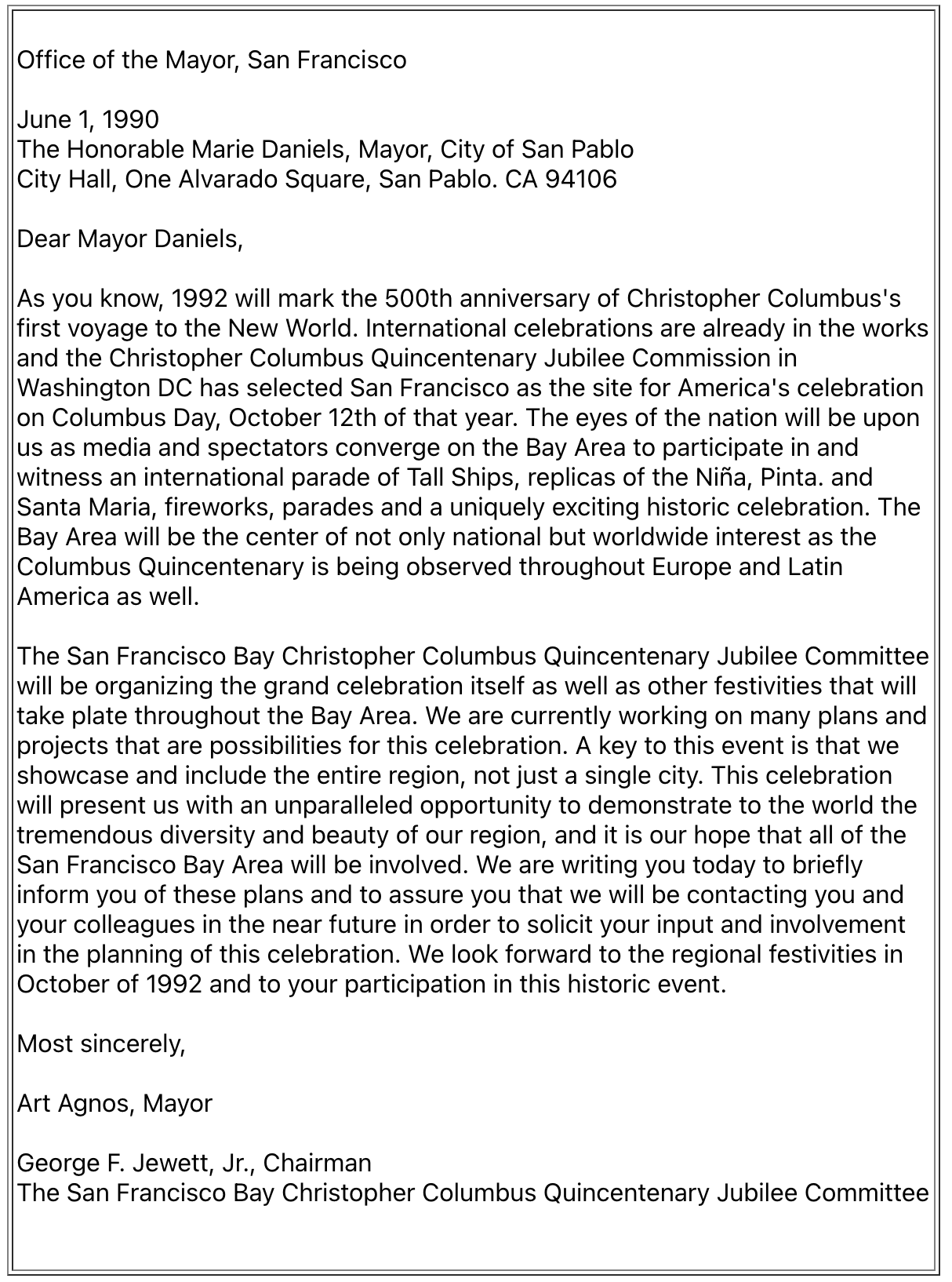

The Christopher Columbus Quincentenary Jubilee Commission was established in 1984, consisting of 30 members with the mission of planning the commemoration. The original deal had been that Spain would build the ships (at the cost of $15 million), and the Commission would organize the US tour, which Texaco would sponsor to the tune of $5 million, with $850,000 going to the Commission. But Texaco pulled out, leaving the Commission holding the bag. Between 1986 and 1990 the government gave the Commission over $1 million to play with, with the rest of their budget to be filled in from corporate donations. But by 1990 they were in a $700,000 hole, with the first director resigning under charges of financial misconduct. Still they conjured up a new chair and soldiered on.

The ships were scheduled to arrive in Miami in February, 1992, as the first stop in a 20-city U.S. tour. Expenses would be absorbed by the cities benefitting from the tour. From Miami they would sail into the Gulf with stops in Corpus Christi, Galveston, New Orleans, and Tampa. Then up the Atlantic coast: St. Augustine, Charleston, Norfolk, Baltimore, Annapolis, Philadelphia, Wilmington, Atlantic City, New York City, New London, and wind up in Boston in August. From there they would be hoisted onto barges, towed through the Panama Canal, up the west coast and let loose in San Francisco Bay on October 12, 1992 as the national focal point and centerpiece of the grand celebration and hoopla. Eventually the ships would continue their historical voyage down the Pacific coast, stopping at San Luis Obispo, Los Angeles, San Juan de Capistrano and finally docking in San Diego.

To organize the Bay Area activities, an independent non-profit committee was set up under the joint honorary chair of the mayors of San Francisco, Oakland, and San Jose, and told it needed to raise and contribute $1.5 million.

In June, 1990, San Francisco Mayor Art Agnos and George F Jewett, Jr., Chairman of the San Francisco Bay Christopher Columbus Quincentenary Jubilee Committee, trying to drum up enthusiasm and support, sent the following letter to other Bay Area mayors:

Oakland Tribune

So two months before the quincentenary, they folded. The whole elaborate shebang was cancelled. We had won.

In an article about it, the Oakland Tribune wrote,

The cancellation was called a minor victory by opponents of the traditional Columbus Day holiday who would rather celebrate the lives of the indigenous people — whose fates were forever changed by Columbus’ landing. Lee Sprague, a Native American artist, saw the ships on their visit to New York, and hated the thought of them coming to the Bay Area. “The Columbus ships were the forerunners of these huge military aircraft carriers. They were both the instruments of suppression and occupation.”

The truth was that the San Francisco Bay Christopher Columbus Quincentenary Jubilee Committee, and the other west coast cities, had all been unable to raise any funds, much less $1.5 million, because Resistance 500 and all our associated groups had done our job well.

The people of the Bay Area didn’t want to celebrate what the ships stood for. Instead, we wanted to celebrate Indigenous Peoples Day.

The First Berkeley Indigenous Peoples Day

The schedule of the first Berkeley Indigenous Peoples Day began to take shape.

Dennis Jennings, Bernadette Zambrano and Sal García designed and produced a large poster.

Berkeley’s Quincentennial Commemoration of

the 500 years 1492-1992

will be held on the first

INDIGENOUS PEOPLES DAY

Saturday, October 10, 1992

with Representatives from many of

the Native Nations

of Turtle Island

(Continental America)

Sunrise ceremony at the waterfront.

12 noon to 4 pm: commemoration activities in

Martin Luther King, Jr. Park (Allston Way and M.L.K. Way),

with cultural presentations by Indigenous people and

participation by the Berkeley schools.

The Turtle Island Monument and time capsule

storing Native thoughts and artifacts will be dedicated.

Booths selling Indigenous food and crafts; informational tables

from Native, Environmental, and Human Rights groups.

At 2 pm: procession leaves the park and slowly circles

to Shattuck Avenue, with art installations and cultural presentations

at each street corner on themes relating to the 500 years

of Indigenous struggle and resistance to colonialism.

The procession will circle back to the park for closing ceremonies.

This event can begin a profound annual tradition in Berkeley,

refocusing social consciousness

toward the nurturing leadership of Indigenous tradition

in harmony with the natural environment.

Indigenous People’s Day

To express appreciation for our survival and acknowledgement of our contribution to today’s world commmunity and in commemoration of our fallen patriots.

Sunrise—Ceremony at the Berkeley waterfront

10:00 AM—Gather in the park

Noon—Dedication of the Turtle Island Monument

2:00 PM—Motorcade leaves

2:00 to 4:00 Procession to Shattuck Avenue.

The text at the bottom:

—Purpose —

1. A commemoration of the now extinguished fires of native nations

long gone and of the indigenous patriots and martyrs who stood for

the values of Indigenous people.

2. To acknowledge the contributions of indigenous peoples to today’s

modern society in arts, medicine, education, science; agriculture and

government.

3. To affirm the survival and existence of tribal peoples all over the

globe and to educate the public of the importance and symbiotic

nature of our common destiny and that of the natural world.

We continued organizing for the day’s events.

The Procession and Indigenous Peoples’ Parade

We planned the Procession and Indigenous Peoples Parade as a version of the Chasky. We would bring the event downtown into the heart of the city. The City agreed to block off three blocks of Shattuck Avenue, from Allston Way to Kitteridge Street, between 2 and 4 pm. It was a moving cultural festival, with music, speakers, poetry, street theatre, informational tables and crafts booths. The procession left the park, walked to Shatuck, and continued down the blocks, stopping for each event, until we reached the Main Library, where we circled back to the park for closing ceremonies.

Included in the Procession and Tabling were Grupo Maya Kusmej Junan, Antenna Theater, Without Reserve, Earth Circus, Pearl Ubungen Dancers. Musicians Yahuar Wauky, Ingor Gaup, Mahal, Will Knapp. Big Mountain Support Group, Guatemala News and Information Center, PEN Oakland, AWAIR, Roots Against War, Middle East Children’s Alliance, Western Shoshone (100th Monkey), Rainforest Action Network, ACD, Ecology Center, Sarah James’ Alaskan Native group, Chicano Human Rights Council, Berkeley Citizens Action, Earth Island Institute, Sister City El Salvador, Oyate, Ecumenical Peace Institute, Real Magic, Cop Watch, Bay Area Landwatch, Labor Committee on the Middle East, Heyday Books/News from Native California. Poets Odelia Rodriguez, Dennis Jennings, Sheila Medina, Floyd Salas, John Curl. Speaking on Shatttuck Avenue were Millie Ketcheshawno, Gabriel Hernandez, Lee Sprague, Dennis Jennings, Roberto García, Mark Gorrell.

Towards the end of the events, a Motorcade would leave to take the elders and dignitaries who participated in the earlier Turtle Island Monument dedication ceremonies down to Intertribal Friendship House in Oakland, where they would join the events that the Bay Area Regional Indian Alliance was organized there, the “1st Nations Intertribal Gathering,” with the theme “Truth In History.” The IFH event, running 12 noon to sundown, at 4 pm would hold a reception for the Indian Nations representatives arriving from the Berkeley Turtle Island Monument dedication. At the same time that Dennis Jennings was our Berkeley coordinator, he and others were also members of the BARIA organizaing group.

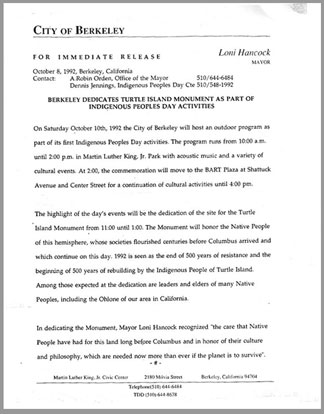

The mayor’s office sent out a press release for the Turtle Island Monument dedication ceremonies:

The Sunrise Ceremony

The sunrise ceremony, presided over by Galeson EagleStar, took place on a hill at Cesar Chavez Park at the Berkeley waterfront.

The dedication of the Turtle Island Monument at the first Berkeley Indigenous Peoples Day:

Other 1992 Resistance 500 Events

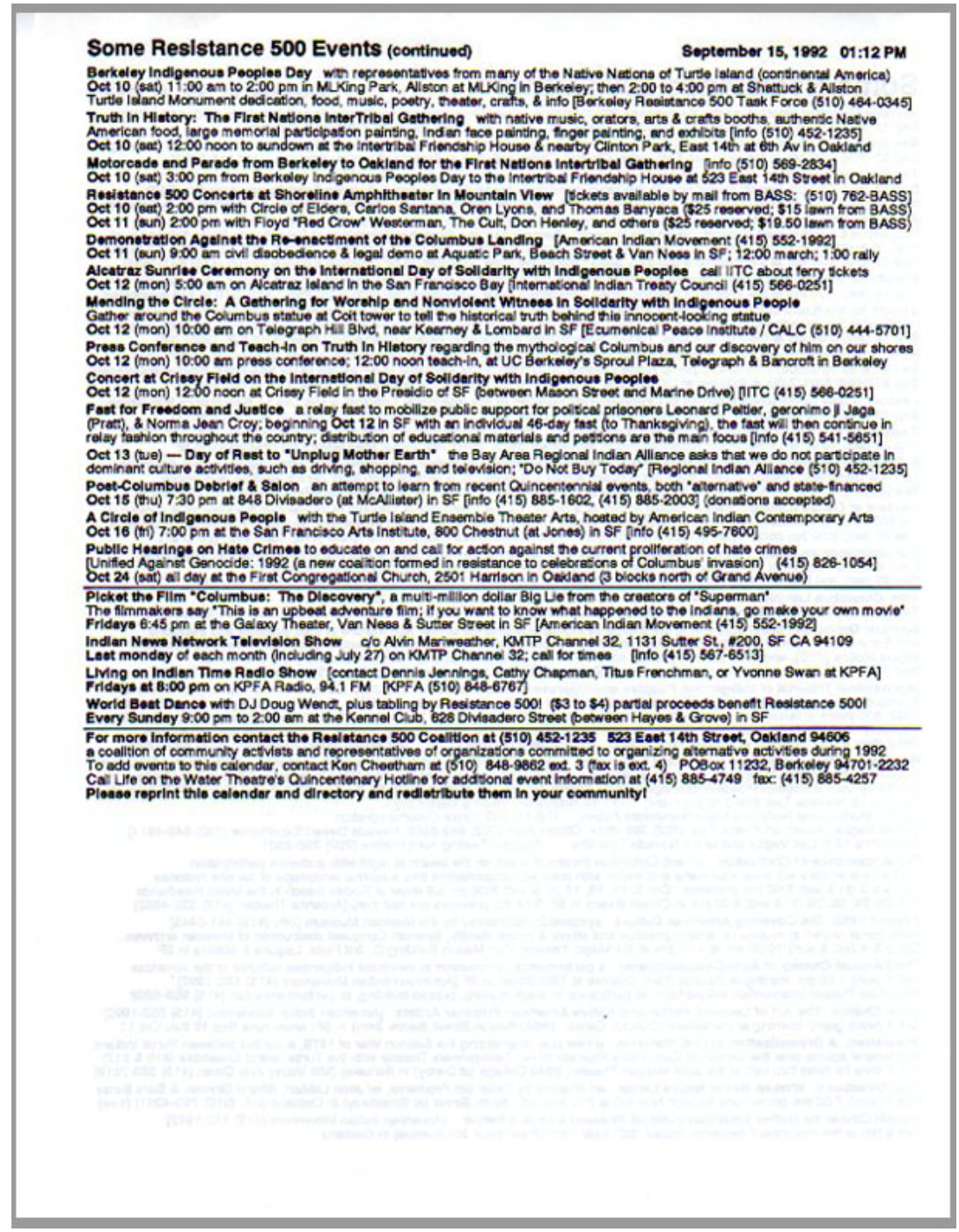

Numerous other Resistance 500 events were taking place in the Bay Area and elsewhere. Here are a few of them. [4]

Chasky

On Saturday, October 4, the week before the quincentenary, the third Chasky was held in San Francisco. It began in Dolores Park, and again finished in La Raza Park with rituals, music, poetry, dance, and speakers. The performance installations en route were again coordinated by Luis Vasquez, and included Wise Fool Puppet Intervention, Teatro ng Tanan, Pearl Ubungen Dancers, Earth Circus, Francisco X. Alarcon, Roots Against War, Grupo Maya Kusamej Junan, and others. But after the fourth Chasky in 1993, the organizing group disbanded, and spoke of having lost direction, perhaps because the event was more focused on opposition than on positive energies working to shape the future. (It was however revived one more time in 2000.)

AIM Tribunal

Between October 9 – 11, the Amercan Indian Movement (AIM) organized a three-day International Tribunal of Indigenous People and Oppressed Nationalities in the USA.

IITC Conference and Concerts

The Treaty Council also sponsored three days of Resistance 500 concerts.

The first two were at Shoreline Ampitheater in Mountain View. On October 10 was All Our Colors: the Good Road Concert, with Circle of Elders, Carlos Santana, Oren Lyons, Thomas Banyaca John Trudell, The Wagon Burners, Jackson Browne, Mickey Hart. John Lee Hooker, Red Thunder, and others. On October 11 was Healing the Sacred Hoop: The Next 500 Years, with Floyd “Red Crow” Westerman, Bonnie Raitt, Buffy Sainte-Marie, The Cult, Don Henley, and others. On October 12, they offered a free concert at Crissy Field in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, with many of the same performers.

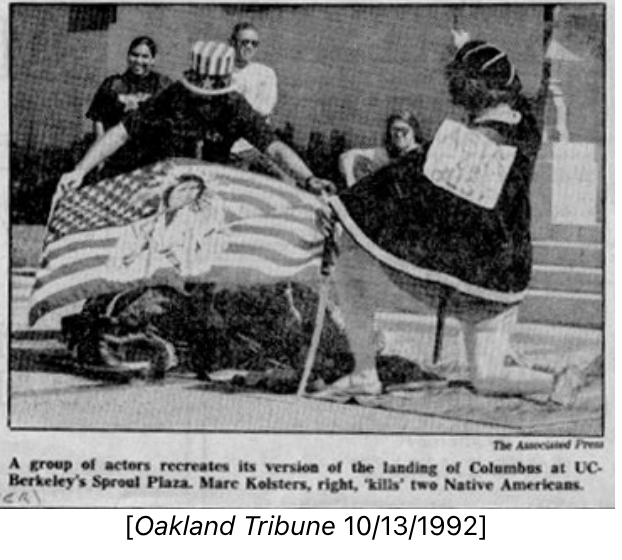

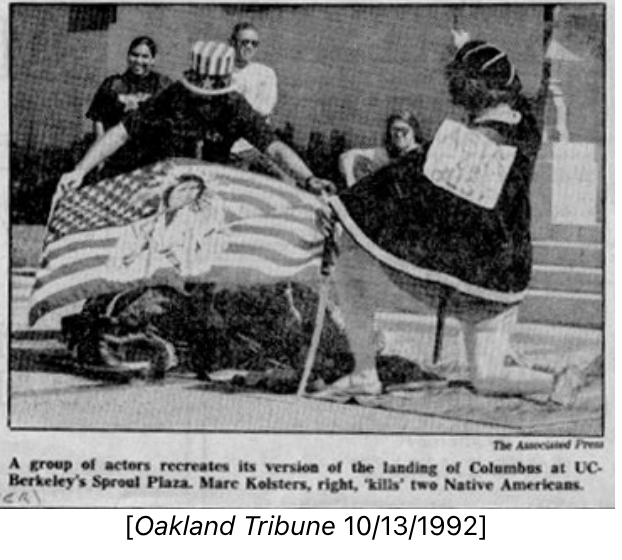

AIM Demonstration Against the Re-enactment

Undaunted by the cancellation of the arrival of the Columbus ship replicas, the San Francisco Italian-American community carried on with plans for their traditional Columbus Day Parade and Re-enactment of the Columbus Landing at Aquatic Park, in which a local dressed up in a Columbus costume arrives in a small boat, falls on one knee and claims San Francisco for the King and Queen of Spain. Since they traditionally thought of October 12 as a celebration of Italian-American culture, many of them were extremely dismayed by the situation. (Eventually clearer heads would prevail, and a couple of years later they began to change the name of the occasion to Italian-American Heritage Day.)

On October 11, 1992, AIM held an important Demonstration Against the Re-enactment of the Columbus Landing at Aquatic Park in San Francisco, followed by a march. During the demonstration the Peace Navy, with over 150 boats, strung ropes between their vessels, and actually prevented the Columbus boat from landing. After that, we marched in a counter-parade.

Alcatraz Sunrise Ceremony

1992 Sunrise Ceremony on Alcatraz Island [Oakland Tribune 10/13/92]

UC Teach-In

On October 12 a teach-in was held at UC Berkeley’s Sproul Plaza on Truth In History.

UnPlug North America

On October 13 the Bay Area Regional Indian Alliance (BARIA) and the Indigenous Environmental Network sponsored a Day of Rest to Unplug North America to Give Mother Earth A Rest, originally initiated by the Indigenous Environmental Network. They asked that we “not participate in dominant culture activities,” to use only sustainable energy, and to not conduct any business transactions.

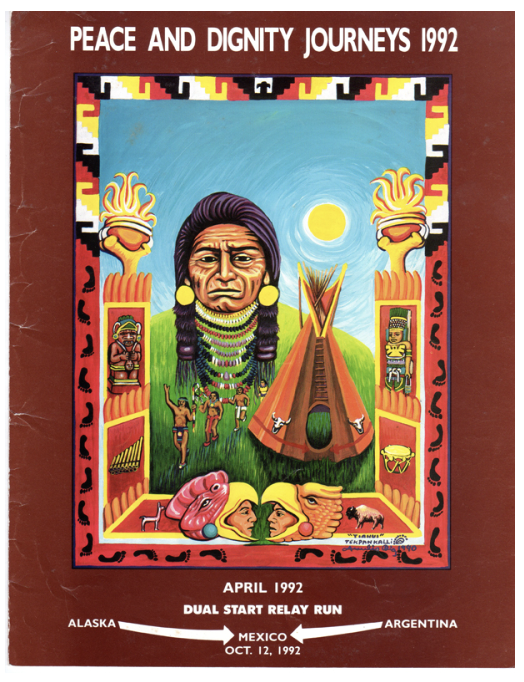

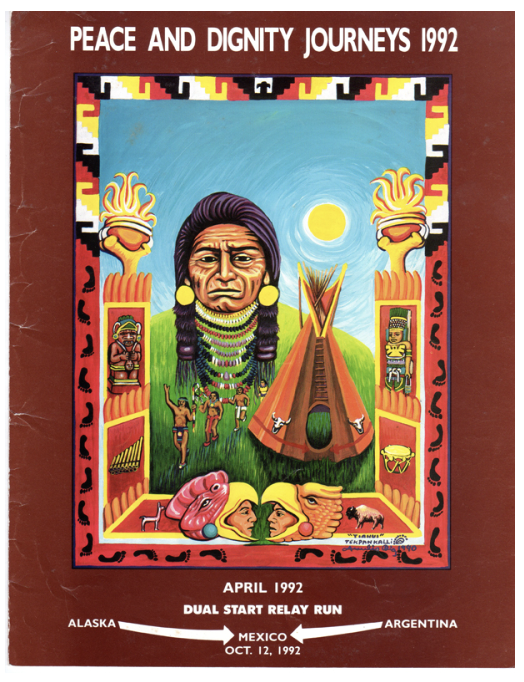

Peace and Dignity Journeys

Peace and Dignity Journeys considered one source of their inspiration to be the Andean prophesy of the condor and eagle, and also looked to prophesies of spiritual running passed down from elders in many parts of the Americas. Those prophesies foretold that spiritual running would help the Native nations to reunite: “we are like a body that was broken up into pieces and this body will come back together to be whole again.” Dorinda Moreno, of Hi-Tec Aztec Productions, was a key Northern California organizer. Their first run in 1992 was to be “a prayer to heal our nations” and the world. The plan was that runners would begin in April 1992 from Alaska running south and from Argentina running north. The runners would pass through numerous Indigenous communities, where they would share wisdom and collect ceremonial objects symbolically containing the prayers of all the many Native peoples, and all would come together for final ceremonies at the base of the Pyramid of the Sun in Teothuacan, Mexico on October 12, 1992. The first Peace & Dignity Journey of 1992 was a great success, and would be renewed with a run every four years thereafter.

LOOKING FORWARD

By the end of October, 1992, the mission of the Berkeley Resistance 500 Task Force was over. Berkeley had become the first city in the world to get rid of Columbus Day and annually commemorate October 12 as Indigenous Peoples Day. [4]

Our group made a smooth transition. We became the Indigenous Peoples Day Commmittee, and as such in 1993 we decided that the most appropriate way to celebrate was with a pow wow, so geared up again to organize the first Berkeley Indigenous Peoples Day Pow Wow and Indian Market.

The Sunrise Ceremony

The sunrise ceremony, presided over by Galeson EagleStar, took place on a hill at Cesar Chavez Park at the Berkeley waterfront.

The dedication of the Turtle Island Monument at the first Berkeley Indigenous Peoples Day:

Other 1992 Resistance 500 Events

Numerous other Resistance 500 events were taking place in the Bay Area and elsewhere. Here are a few of them. [4]

Chasky

On Saturday, October 4, the week before the quincentenary, the third Chasky was held in San Francisco. It began in Dolores Park, and again finished in La Raza Park with rituals, music, poetry, dance, and speakers. The performance installations en route were again coordinated by Luis Vasquez, and included Wise Fool Puppet Intervention, Teatro ng Tanan, Pearl Ubungen Dancers, Earth Circus, Francisco X. Alarcon, Roots Against War, Grupo Maya Kusamej Junan, and others. But after the fourth Chasky in 1993, the organizing group disbanded, and spoke of having lost direction, perhaps because the event was more focused on opposition than on positive energies working to shape the future. (It was however revived one more time in 2000.)

AIM Tribunal

Between October 9 – 11, the Amercan Indian Movement (AIM) organized a three-day International Tribunal of Indigenous People and Oppressed Nationalities in the USA.

IITC Conference and Concerts

The Treaty Council also sponsored three days of Resistance 500 concerts.

The first two were at Shoreline Ampitheater in Mountain View. On October 10 was All Our Colors: the Good Road Concert, with Circle of Elders, Carlos Santana, Oren Lyons, Thomas Banyaca John Trudell, The Wagon Burners, Jackson Browne, Mickey Hart. John Lee Hooker, Red Thunder, and others. On October 11 was Healing the Sacred Hoop: The Next 500 Years, with Floyd “Red Crow” Westerman, Bonnie Raitt, Buffy Sainte-Marie, The Cult, Don Henley, and others. On October 12, they offered a free concert at Crissy Field in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, with many of the same performers.

AIM Demonstration Against the Re-enactment

Undaunted by the cancellation of the arrival of the Columbus ship replicas, the San Francisco Italian-American community carried on with plans for their traditional Columbus Day Parade and Re-enactment of the Columbus Landing at Aquatic Park, in which a local dressed up in a Columbus costume arrives in a small boat, falls on one knee and claims San Francisco for the King and Queen of Spain. Since they traditionally thought of October 12 as a celebration of Italian-American culture, many of them were extremely dismayed by the situation. (Eventually clearer heads would prevail, and a couple of years later they began to change the name of the occasion to Italian-American Heritage Day.)

On October 11, 1992, AIM held an important Demonstration Against the Re-enactment of the Columbus Landing at Aquatic Park in San Francisco, followed by a march. During the demonstration the Peace Navy, with over 150 boats, strung ropes between their vessels, and actually prevented the Columbus boat from landing. After that, we marched in a counter-parade.

Alcatraz Sunrise Ceremony

1992 Sunrise Ceremony on Alcatraz Island [Oakland Tribune 10/13/92]

UC Teach-In

On October 12 a teach-in was held at UC Berkeley’s Sproul Plaza on Truth In History.

UnPlug North America

On October 13 the Bay Area Regional Indian Alliance (BARIA) and the Indigenous Environmental Network sponsored a Day of Rest to Unplug North America to Give Mother Earth A Rest, originally initiated by the Indigenous Environmental Network. They asked that we “not participate in dominant culture activities,” to use only sustainable energy, and to not conduct any business transactions.

Peace and Dignity Journeys

Peace and Dignity Journeys considered one source of their inspiration to be the Andean prophesy of the condor and eagle, and also looked to prophesies of spiritual running passed down from elders in many parts of the Americas. Those prophesies foretold that spiritual running would help the Native nations to reunite: “we are like a body that was broken up into pieces and this body will come back together to be whole again.” Dorinda Moreno, of Hi-Tec Aztec Productions, was a key Northern California organizer. Their first run in 1992 was to be “a prayer to heal our nations” and the world. The plan was that runners would begin in April 1992 from Alaska running south and from Argentina running north. The runners would pass through numerous Indigenous communities, where they would share wisdom and collect ceremonial objects symbolically containing the prayers of all the many Native peoples, and all would come together for final ceremonies at the base of the Pyramid of the Sun in Teothuacan, Mexico on October 12, 1992. The first Peace & Dignity Journey of 1992 was a great success, and would be renewed with a run every four years thereafter.

LOOKING FORWARD

By the end of October, 1992, the mission of the Berkeley Resistance 500 Task Force was over. Berkeley had become the first city in the world to get rid of Columbus Day and annually commemorate October 12 as Indigenous Peoples Day. [4]

Our group made a smooth transition. We became the Indigenous Peoples Day Commmittee, and as such in 1993 we decided that the most appropriate way to celebrate was with a pow wow, so geared up again to organize the first Berkeley Indigenous Peoples Day Pow Wow and Indian Market.

NOTES

1. Unless otherwise stated, all photos are by Nancy Gorrell or from her photo collection.

2. The following year, in 1991, IITC would bring back their proposals that the UN declare a Decade of Indigenous Peoples and International Indigenous Peoples Day. The IITC proposals would finally surface in the General Assembly in December, 1994, and UN Resolution 49/214 would declare 1995 – 2005 to be the International Decade of the World’s Indigenous People. That was a great accomplishment. But the conservative governments, led by the USA, would not touch October 12 and the concept of peoples, and instead removed the “s” of peoples, and declared the innocuous date of August 9 to be International Day of the World’s Indigenous People. However, the governments could not derail the movement to celebrate October 12 as Indigenous Peoples Day in place of a celebration of Columbus’s colonial and imperialist enterprise.

3. “The Birth of Resistance 500,” by John Curl, Huricán (Alliance for Cultural Democracy), Vol 2, No. 1 & 2, Summer 1991, 3.

4. After 1992, many of the Bay Area groups which were active in Indigenous Peoples Day and Resistance 500 between 1990-1992, shifted their focus. The South and Meso-American Indian Information Center (SAIIC) closed in 1999 after Nilo Cayuqueo, the director, returned to Argentina. The Alliance for Cultural Democracy (ACD) disbanded in 1996.