Celebrating Indigenous Heritage

Archives of Indigenous Peoples Day

Celebrate this annual holiday with us in honor of all of our ancestors, the people continuing the struggle today and future generations.

Part 4 - The First Indigenous Peoples' Day PowWow 1993

The pow wow circle in ML King, Jr. Civic Center Park, Berkeley

The morning would begin, as the previous year, with a sunrise ceremony at the waterfront.

Events in the park would start at 10 am, with an invocation by Diane Bowers of the Yurok Nation, part of our successful campaign for a sister community relationship between Berkeley and the Yurok tribe. She would be followed by exhibition dancers: first the Yuroks, then Aztec dancers, Mayan deer dancers by Grupo Maya Kusamej Junan, Hintel Pomo dancers. At noon would be Gourd dancing. The Grand Entry would take place at 1 pm, followed by welcoming words by Mayor Loni Hancock, Councilmember Nancy Skinner, and Yurok representative Diane Bowers. The rest of the afternoon would be Contest dancing, intertribal dancing, round dancing, and guest speakers. After the announcement of the Contest Dance winners, the pow wow would end with a Victory/Flag Dance.

We would make tee shirts with the turtle logo on the front. Raffle prizes would include a Pendleton blanket for first prise and a handmade star quilt for second prize.

After the pow wow would would stage a turkey feast, and give dinner to everyone in the park.

We would make 30-foot banner, which we would hang across Shattuck Avenue, the central downtown street, announcing Indigenous Peoples Day to the community.

We would also sponser Watershed, a drama written by Steve Most, about the Yuroks and the Salmon War of 1978, which would be performed for three days before the pow wow at the Little Berkeley Theater. Performers included Jack Kohler (Yurok/) as the lead, and Nanette Deetz (Dakota/Cherokee/German), who both also visited classrooms in Berkeley High School sharing Native culture.

On the day after the pow wow, on Sunday, we would cosponsor a World Culture Concert in Honor of Indigenous Peoples Day at Peoples’ Park (across town closer to the university). Performers would include All Nations Drum, Aztlan Nation (rap), Bozone (reggae), Ogi Johnson (flute) Karumata (Andean), WithOut Reservation (rap). Lee Sprague would speak. Like the pow wow, there would be vendors and food booths. Cosponsors of the World Culture Concert would be the Ecology Center/Farmers Market, Rock Against Racism, and Children’s Light.

Turtle Logo

When we transformed from Resistance 500 into the Indigenous Peoples Day Committee, we also changed our logo. At that time we didn’t yet have permission of the 1990 Encuentro artist to use the condor and eagle. So our first logo as the IPDC was the Turtle Island turtle with a map of the Americas of its shell, which had been used as a logo by the Bay Area Regional Indian Alliance (BARIA), and which we received permission to use. By the next year we got permission to use the condor and eagle, so we ultimately combined the two designs into the logo that we continue to use today, over two decades later.

The turtle island logo and the eagle-condor symbol remind us of our place in the larger cultural renewal of Native people, and the gifts they bring of a consciousness that is deeply changing a world in desperate need of change. Each Indigenous Peoples Day Pow Wow contributes to that cultural renewal, and increasingly does its small part. Learning how to live in indigenous ways may not come easy to many people of European backgrounds, emerging from a long history of glorifying aggressive domination. But every year the pow wow brings the power of Native people to Berkeley, increasingly impacting the world with a living philosophy of peace, community, and sustainability.

Pow Wows

When I lived in the Southwest between 1966 and 1971, pow wow’s weren’t big events, or at least I didn’t connect with them. I attended a Ute sundance, ceremonies at Taos and other Pueblos, and for a year I worked on the To’Hajiilee Navajo (Diné) reservation, where I attended a Yeibichei and many other Navajo healing ceremonies. Since I’d been in California, I’d been to a Miwok Big Time. But never a pow wow.

I now began to learn something about pow wows, and why they were so relevant to what we were doing.

While their roots are very old, they are also new. They only became widespread as part of the rejuvenation and resurgence of Native culture in the 1970s after the Alcatraz occupation. They became a cultural meeting place for people of many tribes and Native nations, a strong expression of the new intertribal identity that Native people were forging in that era. Pow wows also became a place where Native people welcome non-Natives, where all people of good will can come together, dance together, socialize, and participate in Indigenous culture. Where nonNatives can interact with Native people and get to know them. Pow wows include dancing competitions, with prize money, and an Indian market with Native food and crafts.

We planned the Berkeley Pow Wow for just one day, but some of the biggest ones last a full week.

Origins of the Pow Wow

Many tribes trace pow wows back to their own periodic gatherings, large traditional celebratory feasts, usually after the fall harvest. The oldest continuous annual pow wow today is probably the Quapaw, now in its 138th year in Oklahoma. The term pow wow comes from an Algonquian word for a gathering of people, which began to be used in Oklahoma around 1900.

Diverse tribes have different stories about the origin of pow wow dancing. There are distinct northern and southern traditions. One commonly told origin story among southern tribes holds that the first pow wow dance was the Iruska, a dance of the Pawnee, taught to a man named Crow Feather by a group of spiritual beings who immersed their hands into boiling water and fire. Iruska means “they are inside the fire,” but is often translated as “warrior.” The dance is usually known today as the Warrior or Straight Dance. The beings held Crow Feather over hot coals, and after he survived, they taught him songs and the dance, and told him to teach them to the people. Then the beings turned into birds and animals and left. On a second night they returned and repeated the ceremony. At the end, one spiritual being stayed behind and taught Crow Feather to make many of the symbolic items worn today by male pow wow dancers. His “crow belt” is today the back bustle worn by Fancy dancers. His “roach headdress,” made from deer and porcupine hair, represents the fire ordeal: an eagle feather in a deer shoulder blade represents the man standing in the center of the fire; the bone also represents the medicine given to him.

In the early twentieth century the dance spread out of Oklahoma through the Great Plains north to Canada. Dance societies were formed in over thirty Plains tribes, and through the dance former enemies made peace. Pow wows gained momentum after World War II, when they were held as local honoring ceremonies for returning Indian veterans. In the mid-1950s many Native people began traveling between communities, dancing in pow wows and promoting Intertribal culture. But, as I already reported, they weren’t very prominent until after the Alcatraz occupation of 1969-1971, when an intense intertribalism revitalized Native culture.

With time and many different tribes adding their individual characters to the dance, the Iruska took a variety of forms: Grass Dance, Fancy Dance, the Northern and Southern Traditional, and many more. At first women did not dance, but today women have a wide variety of dances, including the Jingle Dance, Shawl Dance, and forms of the Northern and Southern Traditional.

Pow wow dancing today is based on spiritual values, the commemoration of warriors who struggled for their people, former enemies dancing together, peacemakers and peace, cultural survival and spiritual resurgence.

The Pow Wow Circle

That first year of our Berkeley pow wow in 1993 (and every year since,) we borrowed a chalker from the city parks department—the kind with wheels that they use for marking softball playing fields—to lay out the pow wow circle. In the late afternoon of the day before the event, our pow wow committee met on the grassy lawn of Civic Center Park. We brought a rope about 12 paces long, the chalker, and a large bag of powdered chalk. We needed to explain what were doing to all the high school students and others relaxing there or playing Frisbee (Berkeley High School is across the street). Once they understood, they gladly moved to one side so we could chalk the circle.

One member of the committee held an end of the rope in the exact center of the park. We tied the other end of the rope to the handle of the chalker, and Mark Gorrell pushed it in a perfect circle with about a 60 foot diameter. On the east end of the circle he chalked a turtle’s head, facing the fountain dedicated as the Turtle Island Monument, on the west end a tail, and four turtle feet in between. It became a special place, the turtle pow wow arena circle, representing the American continent. Mark Gorrell performed that task from the first pow wow until his untimely passing.

The pow wow dancers dance inside the turtle circle, and at particular times the MC also invites all spectators into the circle to join in certain dances.

That first pow wow in 1993 set a pattern we would follow every year after.

The turtle’s head marks the entrance into the arena. To one side are tables for the MC, the arena director, the coordinator, and other organizers. Posted near the MC table are an eagle staff and flags, including the US flag. These will be carried around the dance circle by honored elders during the Grand Entry at the beginning of the pow wow, and at the closing. The eagle staff, a high curved wooden staff with eagle feathers attached, can be thought of as the Native American flag.

At the south end of the turtle circle is the host southern drum, and at the north end is the host northern drum. The northern and southern drums represent different styles and traditions.

Continuing around the dance circle are shade canopies where the dancers and their families and friends rest between events. The circle beyond that is a walkway, and finally the outside circles consist of Native vendors selling arts and craft items, mostly hand made, and Indigenous food.

Inside and around the pow wow circle violence, drugs, or alcohol are never permitted. The arena has been blessed with prayer and sage; it has taken on a special atmosphere and become spiritual ground.

The Drums

Pow wows often have two host drums, one Southern and one Northern. All other drums are invited, and some often show up unannounced. The drums usually take turns, unless the MC or arena director specifically asks one drum to play a particular song.

Many drums travel from powwow to powwow each week and are in high demand. Many have recording contracts, and each year drum groups are nominated for Grammy awards in the Native American category.

The drum is heartbeat of the pow wow.

Each drum has a lead singer and a second lead. The lead singer is responsible for knowing any kind of song requested by the MC or arena director. When the lead singer sings a line, the second lead usually repeats it in a variant key.

There are two basic styles of pow wow drumming and singing, Southern and Northern. These are not geographical locations so much as different styles and arrangements. Southern singing is in a lower pitch and slower than Northern, which is often in a high fast falsetto. Songs are usually in Native languages. Sometimes the songs are not in words at all, but in vocables, syllables of sound carrying the melody and meaning.

A pow wow drum is considered a sacred instrument. In many tribal traditions it is never left unattended, nothing is ever placed on top of it, and no one can reach across it. It is constructed with a wooden shell covered on both ends by the stretched hide of a deer, buffalo, elk, or steer. The tension on the drum heads tune it, determining pitch and voice. Usually about 26 – 32 inches across, standing off the ground, it is large enough for five to ten people to sit around. There are usually at least four drummers, one for each of the directions. The drummers beat it in unison with hide-covered sticks. They are also singers, and their song arises from their unique blend of voices and drumming. Each group of singers is called “a drum.” Most drums are all men, but some have women members and some are all women. Drummers usually dress in ordinary clothes. Most drum carriers and singers have studied many years learning the traditions and the songs. Many of the songs have been passed down for unknown generations, while some are recent. During a song, there will be occasional “honor” beats, louder and in a slower tempo, which are said to be done out of respect for the drum. A single drum beat supposedly represents Mother Earth and a double drum beat represents human beings. Every pow wow drum is said to contain its own spirit, so the singers must comport themselves with traditional dignity around it.

Numerous stories are told about pow wow drums, that a woman’s spirit lives inside them, that they place the people in touch with their heart, bringing balance, life, and spirituality, that they channel ancestral voices to heal the people and the earth, that the drum carries its beat down into the heart of the planet, and returns carrying the earth’s heartbeat up into the pow wow, summoning the people together and harmonizing them.

The Dancers

Dawn on pow wow day greets the vendors, many coming from long distances, setting up booths displaying an amazing array of craft items and traditional foods. With them is the vendors coordinator Hallie Frazer and her clip board, straightening out any confusion about spaces and checking that all the booths are carrying only creations hand made by Native people. Every vendor contributes a piece to the raffle, and winners are announced throughout the day.

Around 10 am traditional elders bless the grounds. Then exhibition dancing begins, from traditions outside the dances of the pow wow proper. People who arrive later miss this extraordinary segment. Native California Indians dance first, since it is their land and we are their guests. Traditional Pomo dancers, feather bands across their foreheads, feathered robes and skirts, bone whistles, barefoot and crouched, stomping deep into the earth, hunting, praying. Then the Aztec dancers, conch shell trumpets to the four directions, long feathers swooping to the beat of the tall upright drum, connecting earth and sky, keeping the stars, planets, celestial forces in their proper motion, balance and harmony.

The Open Gourd Dancing begins. Because of its particular spiritual significance, no filming is permitted. Led by the Head Gourd Dancer, the dancers, usually with a red and blue blanket over their shoulders, holding metal or gourd rattles and feather fans, find places near the perimeter of the circle. They dance in place or nearby, shaking the rattles in a horizontal motion, lifting their feet to the drums in prayer. The pace of the songs starts slowly then picks up as the dance progresses. It is a healing for warriors, a proud, dignified dance.

At noon is the Grand Entry, and the pow wow proper begins. All the dancers line up in a specific order behind elders and veterans carrying the Eagle Staff and flags at the entrance to the arena. This in honor of all the warriors of the past and veterans of today who sacrificed for their people. As a host drum begins a special song, the staff and flag holders lead the procession into the arena and around the circle, slowly moving in a group to the drum beat. A powerful spectacle. Then the MC calls an honored elder forward to give an invocation. As the other host drum plays veterans and victory songs, the staff and flags are positioned at the MC table, and the procession leaves the arena.

The dance circle is blessed by an honored elder. The MC introduces the head staff and visiting dignitaries.

The drum begins again, for either a sneak-up or a round dance. The sneak-up dance is based on scouting animals or rivals. The drum quickens to pitch, suddenly stops, and the dancers need to stop simultaneously. Intertribal Round dances are joyous social occasions, and all people—non-Native and Native alike—are invited into the arena to dance together. Everyone joins hands into a long circle moving around and around. If there are too many, another circle is formed within the first. The round dance transcends all cultures and brings people together.

The Contest dancing begins, organized around dance style, gender, and age. The judges are elders, usually winning dancers. The contest styles are Traditional, Fancy, Grass, Jingle, and Shawl. Pow wow dances today are the result of over a century of evolution through interaction of the Native people of different tribes and nations.

The Tiny Tots come on first, all under 6, some in their first pow wow, always a joy to watch, and everyone’s a winner.

The Head Man and Head Woman Dancers are the first to dance in any song. This is an honor, and head dancers serve as model for all other dancers.

The Men’s Traditional Dance is based on a warrior stalking game or tracking an enemy. The dancer may be wearing a feather bustle and headdress, beaded moccasins, ankle bells, carrying a shield and a dance stick.

Men’s Fancy Dance is strenuous, with intricate footwork. Fancy Dancers spin and leap, wearing brilliant regalia, and two feathered/beaded dance sticks.

Men’s Grass Dance involves swaying and dipping motions. It began as an occasion of flattening plains grass for a camp. Grass dancers wear colorful shirts and pants, with fringes and ribbons, ankle bells, headdress, beaded moccasins.

Ladies Fancy Shawl Dance is based on a butterfly in flight, with highly energetic, intricate footwork involving dips, twirls, spins, and other fancy steps. The dancers wear a fringed shawl with vest and leggings usually adorned with sequins or beads, and a feather in the hair.

The Jingle Dance dress is sewn with row upon row of small metal cones that chime rhythmically, and dancers wear beaded leggings, carry a feather fan and a plume in the hair. The Jingle Dance is associated with healing.

In between contest dances there may be Honor Songs for members of the community who have crossed over in the last year, and Blanket Dances to raise funds for deserving organizations, families in need, visiting drums, or another worthy cause. Every year there are special dances, such as a Two Step/Owl Dance (Ladies Choice); a Potato Dance sponsored by the Black Native American Association, a Switch Dance (women and men exchanging regalia and dancing in each other’s style). We’ve also held Prettiest Shawl contests, which have proved extremely popular.

At various times more intertribal Round dances are held where all people, Native and non-Native dance together.

Toward the end of the day the final raffle winners are announced. The contest winners are called to be honored and receive their prizes. A Thank-you song for the organizing committee.

Finally at 6 pm, as the sun hovers low in the west, the Eagle Staff and the colors are retired, and the Indigenous People Day Pow Wow is ended until next year.

Mitakuye oyasin. For all our relations.

The First IP Day Pow Wow Picture Album

Numerous people have made important contributions to the Indigenous Peoples Day Pow Wow and the IPD Committee over the many years since our first pow wow. There are too many to thank all of you by name here, but your spirit is still very much with us in the smudge circle. Several important members who have recently walked on, Don Littlecloud Davenport, Millie Ketcheshawno, and Mark Gorrell are of course still guiding us.

Indigenous Peoples Day Pow Wow Coordinators

1992 Dennis Jennings

1993 Lee Sprague

1994 John Bellinger

1995-1999 Millie Ketcheshawno

2000-2004 Sharilene Suki

2005-2006 Rochelle Hayes

2007-2015 Gino Barichello

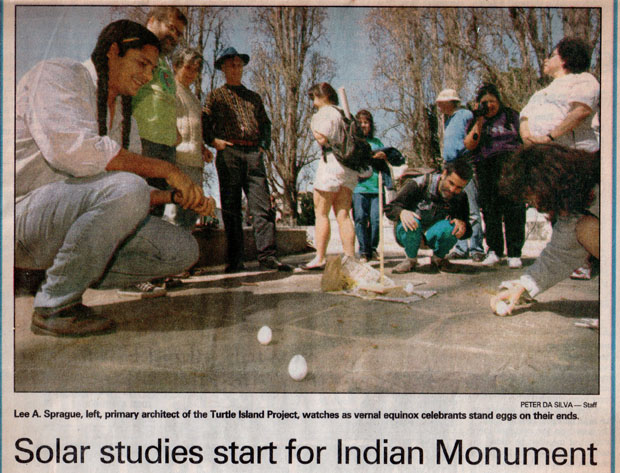

Turtle Island Monument Fountain

Transforming the old broken fountain into the Turtle Island Monument, first proposed by Lee Sprague, was endorsed unanimously by the Berkeley City Council and dedicated by Native elders on the first Indigenous Peoples Day in 1992. The Fountain was conceived as a living symbol of the sustainable way of life practiced by Native People of the American continent, of the continuity between the original inhabitants of this land and the people who have come here from all corners of the globe, and as an inspiration to modern society to create a sustainable future.

But during the city process, several preservationists began to lobby adamantly against the demolition of the old fountain. Finally a compromise was reached. Lee Sprague’s and Marlene Watson’s original drawing had one turtle in the center of the fountain, and medallions with symbols of Native America embedded into the surrounding walkway. Now the old structure of the fountain would be retained and around it turtle sculptures would be installed in the four directions with four medallions between them.

More delays followed. In 2002, on the tenth anniversary of the original dedication, the Turtle Fountain was rededicated at the pow wow by a round dance, in which eveyone could join, led by champion fancy-dancer Gilbert Blacksmith. The following spring, the City set up a Selection Committee to choose an artist and to oversee the completion of the project. The Native representatives on the committee were Sharilene Suki and Janeen Antoine, both highly esteemed in the Native community. In 2005 they chose Scott Parson of South Dakota as the artist. In 2008 Parson’s sculptures and medallions arrived in Berkeley. However, by that time, as the national and world economy crashed, the funds to install the turtles had vanished.

So the turtle sculptures were put on temporary display at city hall, while the medallions remained in their packing crates in a warehose, where they remain today, still waiting installation in their final home around the Turtle Island Fountain.

[Oakland Tribune, March 22, 1994]

[Photo by the City of Berkeley]

[Image: the City of Berkeley]

NOTES

1. All photos by Nancy Gorrell or from her collection unless otherwise marked.