|

Celebrate

this annual

holiday with us in honor of all of our ancestors,

the people continuing the struggle today and future generations. |

|

ARCHIVES

|

|

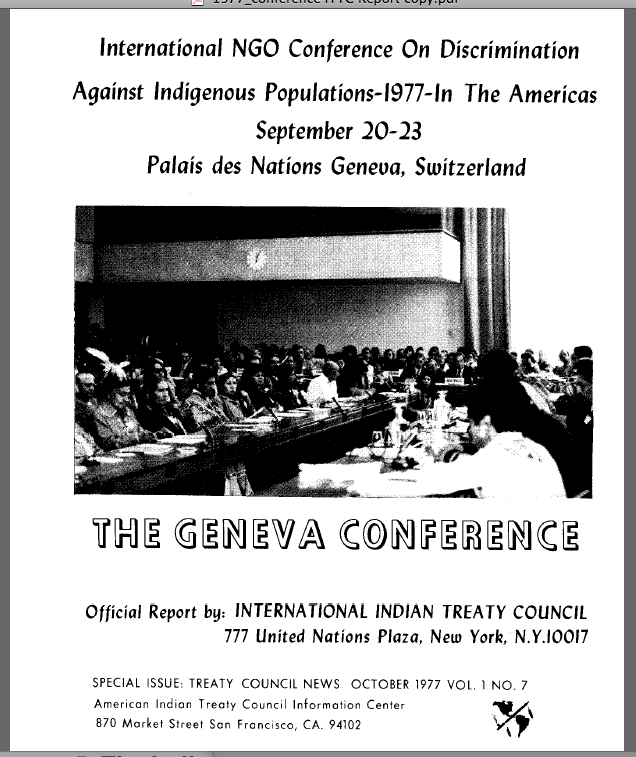

The Final Resolution The International Non-Governmental Organizations Conference on Discrimination against Indigenous Populations 1977 in the Americas brought together more than 250 delegates, observers and guests at the Palais des Nations, Geneva, from 20-23 September, including representatives of more than 50 international nongovernmental organizations. For the first time, the widest and most united representation of indigenous nations and peoples, from the Northern to the most Southern tip and from the far West to the East of the Americas took part in the Conference. They included representatives of more than 60 Nations and peoples, from fifteen countries (Argentina, Bolivia, Canada, Chile, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Ecuador, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama Paraguay, Peru, Surinam, United States of America, Venezuela). It is regretted that some delegates were prevented by their governments from attending. The Director of the United Nations Division on Human Rights addressed the participants on behalf of the United Nations Secretaw-General. Representatives of the United Nations, the International Labour Organization and UNESCO addressed and participated in the conference. The representative of the Consel d’Etat of the Canton of Geneva welcomed the participants. Observers from 38 UN Member States followed the proceedings. The Conference was the fourth such event organized by the Geneva NGO Sub-Committee on Racism, Racial Discrimination, Apartheid and Decolonization of the Special NGO Committee on Human Rights. Previous conferences, all organized within the framework of the United Nations Decade for Action to Combat Racism and Racial Discrimination were, in 1974, against apartheid and colonialism in Africa; in 1975, on discrimination against migrant workers in Europe; in 1976, on the situation of political prisoners in southern Africa. The representatives of the indigenous peoples gave evidence to the international community of the ways in which discrimination, genocide and ethnocide operated. While the situation may vary from country to country, the roots are common to all; they include the brutal colonization to open the way for plunder of their land and resources by commercial interests seeking maximum profits; the massacres of millions of native peoples for centuries and the continuous grabbing of their land which deprives them of the possibility of developing their own resources and means of livelihood; the denial of self-determination of indigenous nations and peoples destroying their traditional value system and their social and cultural fabric. The evidence pointed to the continuation of this oppression resulting in the further destruction of the indigenous nations. Many participants expressed support for and solidarity with the indigenous nations and peoples. Three commissions dealt specifically with the legal, economic, and social and cultural aspects of discrimination and formulated recommendations for actions in support of indigenous peoples. Based on these reports, the Conference established a program of actions to be carried out by non-governmental organizations in accordance with their mandates and possibilities: PROGRAMME OF ACTIONS

The Conference recommends: • to observe October 12, the day of so-called “discovery” of America, as an International Day of Solidarity with the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas; • to present the conference documentation to the United Nations Secretary-General and to submit the conclusions and recommendations of the Conference to the appropriate organs of the United Nations; • to study and foster the discussion of the attached Draft Declaration of Principles for the Defense of the Indigenous National and Peoples of the Western Hemisphere, elaborated by indigenous peoples’ representatives; • to take all possible measures to support and defend any participant in the conference who may face harassment and persecution on their return; • to express to ICEM (Intergovernmental Committee for European Migration) the concerns of the Inference about the continued settlement of immigrants on the land of indigenous peoples in the Americas and urge strongly that the resources of ICEM should not be used in support of such immigrants, particularly when coming from the racist regimes of Southern Africa. In the legal field: • that international instruments, particularly IL0 Convention 107, be revised to remove the emphasis on integration as the main approach to indigenous problems and to reinforce the provisions in the Convention for special measures in favour of indigenous peoples; • that the traditional law and customs of indigenous peoples should be respected, including the jurisdiction of their own forums and procedures for applying their law and customs; • that the special relationship of indigenous peoples to their land should be understood and recognized as basic to all their beliefs, customs, traditions and culture; • that the right should be recognized of all indigenous nations or peoples to the return and control, as a minimum, of sufficient and suitable land to enable them to live an economically viable existence in accordance with their own customs and traditions, and to make possible their full development at their own pace. In some cases larger areas may be completely valid and possible of achievement; • that the ownership of land by indigenous peoples should be unrestricted, and should include the ownership and control of all natural resources. The lands, land rights and natural resources of indigenous peoples should not be taken, and their land rights should not be terminated or extinguished without their full and informed consent; • that the right of indigenous peoples to own their land communally and to manage it in accordance with their own traditions and culture should be recognized internationally and nationally, and fully protected by law; • that in appropriate cases aid should be provided to assist indigenous peoples in acquiring the land which they require; • that legal services should be made available to indigenous peoples to assist them in establishing and maintaining their land rights; • that all governments should grant recognition to the organizations of indigenous peoples and should enter into meaningful negotiations with them to resolve their land problems; • that an appeal should be made to all governments of the Western Hemisphere to ratify and apply the following Conventions: (i) Genocide Convention (ii) Anti-Slavery Conventions (iii) Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination (iv) International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (v) International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (vi) American Convention on Human Rights In the economic field: • that the non-governmental organizations widely publicize the results of this conference in order to mobilize support and aid for the indigenous peoples of the Western Hemisphere in their homelands; • that conferences, seminars and colloquia be organized by NCOs, by intergovernmental bodies on all levels - regional, national, global - with the full participation of indigenous people to keep alive the issues that have come to world-wide attention at this conference, and to hear new testimony that will be presented in the future; • to promote the establishment of a working group under the Sub-Commission on the Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights; • to request that the United Nations Special Committee on Decolonization hold hearings on all issues affecting indigenous populations; • that the United Nations Committee on Trans-National Corporations conduct an investigation into the role of multinational corporations in the plunder and exploitation of native lands, resources, and peoples in the Americas. In the social and cultural field: • to promote respect for the cultural and social integrity of indigenous populations of the Americas. Such respect should be especially promoted among local and national governments and appropriate intergovernmental organizations, and be based on the conclusions enunciated in the commission report; • to give all possible financial and moral support to efforts initiated by American Indians in defense of their culture and society, and in particular to the various education programmes launched by Indian movements. Solidarity is also requested for political prisoners and other victims of persecution on account of their participation in such indigenous movements. Many other proposals and recommendations were made by the conference commissions. It is suggested that they be studied by NGOs for the formulation of possible action programs by them. The Conference requests the officers of the Sub-Committee on Racism, Racial Discrimination, Apartheid and Decolonization to promote the decisions of the Conference and to receive and circulate information from NGOs about the implementation of these decisions. |

Draft Declarations of

Principles

for the Defense of the Indigenous Nations

and Peoples of the Western Hemisphere (1) Recognition of Indigenous nations: Indigenous people shall be accorded recognition as nations, and proper subjects of international law, provided the people concerned desire to be recognized as a nation and meet the fundament requirement of nationhood, namely: (a) having a permanent population; (b) having a defined territory; (c) having a government; (d) having the ability to enter into relations with other states. (2) Subjects of International Law: Indigenous groups not meeting the requirements of nationhood are hereby declared to be subjects of international law and are entitled to the protection of this Declaration, provided they are identifiable groups having bonds of language, heritage, tradition, or other common identity. (3) Guarantee of Rights: No indigenous nation or group shall be deemed to have fewer rights or lesser status for the sole reason that the nation or group has not entered into recorded treaties or agreements with any state. (4) Accordance of Independence: Indigenous nations or groups shall be accorded such degree of independence as they may desire in accordance with international law. (5) Treaties and Agreements: Treaties and other agreements entered into by indigenous nations or groups with other states, whether denominated as treaties or otherwise, shall be recognized and applied in the same manner and according to the same international laws and principles as the treaties and agreements entered into by their states. (6) Abrogation of Treaties and other Rights: Treaties and agreements made with indigenous nations or groups shall not be subject to unilateral abrogation. In no event may the municipal laws of any state serve as a defense to the failure to adhere to and perform the terms of treaties and agreements made with indigenous nations or groups. Nor shall any state refuse to recognize and adhere to treaties or other agreements due to changed circumstances where the change in circumstances has been substantially caused by the state asserting that such change has occurred. (7) Jurisdiction: No state shall assert or claim to exercise any right of jurisdiction over any indigenous nation or group unless pursuant to a valid treaty or other agreement freely made with the lawful representatives of indigenous nation or group concerned. All actions on the part of any state which derogate from the indigenous nations’ or groups’ right to exercise self-determination shall be the proper concern of existing international bodies. (8) Claims to Territory: No state shall claim or retain, by right of discovery or otherwise, the territories of an indigenous nation or group, except such lands as may have been lawfully acquired by valid treaty or other cessation freely made. (9) Settlement of Disputes: All states in the Western hemisphere shall establish through negotiations or other appropriate means a procedure for the binding settlement of disputes, claims, or other matters relating to indigenous nations or groups. Such procedures shall be mutually acceptable to the parties, fundamentally fair, and consistent with international law. All procedures presently in existence which do not have the endorsement of the indigenous nations or groups concerned, shall be ended, and new procedures shall be instituted consistent with this Declaration. (10) National and Cultural Integrity: It shall be unlawful for any state to take or permit any action or course of conduct with respect to an indigenous nation or group which will directly or indirectly result in the destruction or disintegration of such indigenous nation or group or otherwise threaten the national or cultural integrity of such nation or group, including, but not limited to, the imposition and support of illegitimate governments and the introduction of non-indigenous religions to indigenous peoples by non-indigenous missionaries. (11) Environmental Protection: It shall be unlawful for any state to make or permit any action or course of conduct with respect to the territories of an indigenous nation or group which will directly or indirectly result in the destruction or deterioration of an indigenous nation or group through the effects of pollution of earth, air, water, or which in any way depletes, displaces or destroys any natural resources or other resources under the dominion of, or vital livelihood of an indigenous nation or group. (12) Indigenous Membership: No state, through legislation, regulation, or other means, shall take actions that interfere with the sovereign power of an indigenous nation or group to determine its own membership. (13) Conclusion: All of the rights and obligations declared herein shall be in addition to all rights and obligations existing under international law. |